Revue des Colonies V.2 N°1 (selection in English translation)

Maria Beliaeva Solomon

Annotated by

A. Lagarde

M. Beliaeva Solomon

A. Louis

A. Brickhouse

Charlotte Joublot Ferré

C. Stieber

E. Hautemont

G. Pierrot

J. Couti

J. Balguy

K. Duke-Bryant

L. Demougin

M. L. Daut

M. Roy

N. Romney

S. E. Johnson

T. Tirkawi

Y. Najm

Publication Information

Information about the source

REVUEDESCOLONIES

MONTHLY COMPENDIUM OF POLITICS, ADMINISTRATION, JUSTICE,

INSTRUCTION AND COLONIAL CUSTOMS,

DIRECTED BY C.-A. BISSETTEC.-A. BISSETTE.

2nd year — n.1 — July.

Am I not a man and your brother?....[26]

PARIS, AT THE OFFICE OF THE REVUE DES COLONIES, 28, RUE LOUIS-LE-GRAND. 1835.

REVUE DES COLONIES

2nd YEAR. JULY 1835. N° 1.

On the abolition of slavery by the National Convention.

— Bill for the abolition of slavery.

— Inquiry into the colonies, Vote on the last law on the colonies.

— Electoral question.

— FRANCE. House of Representatives. Discussion of the budget of the Navy

and the Colonies.

— Of the passing of the law relating to criminal legislation.

— Chamber of Peers.

— Discussion of the law of an additional credit of 650,000

francs granted to the Minister of the Navy and the Colonies.

— Foreign colonies. Bermuda. Barbados.

— Miscellaneous News.

— Varieties.

— Biography.

— Poetry.

— Bibliography.[27]

ON THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY BY THE NATIONAL CONVENTION. — REVUE DES COLONIES

BILL.

Slavery, which is tending to disappear completely and in all its forms from human

societies, and the abolition of which by legislative means in our colonies cannot

be long in coming, was once already outlawed, with admirable spontaneity, by the

National ConventionNational Convention. The National Convention did

not put off this just reparation for an hour, and from the moment that the

question had been submitted, it was resolved without hesitation in the direction

of the revolution and of the philosophical spirit of the eighteenth century;

better said yet, it was not even a question. In the first preoccupations of '89,

the colonies were only considered momentarily. In a rush, free men of color were

called to enjoy the rights of citizenship. In the colonies themselves, the

question, although then as now at the heart of the matter, was kept as far as

possible out of discussion by a kind of apprehension and vague dread of the

future.

However, the French Revolution had taken effect. The new ideas distributed by the

press, spread by the word, had crossed the seas[28]; the French Antilles[29] were also consumed with this new state of mind.

In general, however, it was only among the whites that parties had been formed. In

the colonies as in France there were revolutionaries, and

counter-revolutionaries, supporters of royalty and supporters of democracy. The

tricolor flag had appeared to some as an odious sign, to others, a glorious sign;

the latter were the most numerous, the former the richest. Hence divisions,

parties; a silent disagreement between those who clung desperately to the

privileges of the past, and those whom the breath of new liberty had touched as it

crossed the seas. The debate was still only between them. Of the liberation of

slaves, not a clear and distinct word, as if the rights of man had not been

proclaimed and the Bastille had not been taken. By whatever names the colonists

used, republican or royalist, none among them was led by the spirit of age[30] to draw from the principles that they claimed for themselves,

a conclusion favorable to the freedom of the other race; the distinction of color

remained, slavery was the holy ark which no one dreamed of touching.

However, the counter-revolutionary work advanced, EnglandEngland, then at the head of the retrograde movement, attacked us

everywhere in the two seas. Mistress of MartiniqueMartinique, poorly defended by its inhabitants, of whom several,

and of the highest rank, were traitors to the fatherland (1),[31] England had vainly tried to conquer several other points, including GuadeloupeGuadeloupe and Saint-DomingueSaint-Domingue. Saint-Domingue, however, was seriously threatened.

At the first news of the danger, the National Convention sent two of its members

to organize the defense: they found nothing but dispiritedness.

In the most perilous circumstances, the commissioners had recourse to a great

measure of public safety, completely conforming to the

(1) M. le Chevalier Dubuc, who then was at the head of the colonial

committee in Martinique, crossed furtively to the island of Dominica, whence he

embarked for England, and returned with the English Admiral Gardener to attempt

the conquest of Martinique. This expedition, which was repelled with heavy

losses, did not discourage M. Dubuc; he returned to England, and succeeded in

inducing the British government to grant him, as well as M. de Clairfontaine,

deputy for Guadeloupe, new forces for the conquest of Guadeloupe and

Martinique. A squadron, under the orders of Admiral Jervis, and an army under

the orders of General Grey, seized Martinique in 1794. Guadeloupe thus fell

into the power of the English, but they were driven out forty days

later.

nature of their mission and for which they took full responsibility: they called

the slaves to freedom. The slaves rushed in mass to the defense of the colony, and

from then on the blacks[32] were won over to the great cause of

the French republic.

In the meantime, an election was held in Saint-Domingue in which all classes of

the population took part, without distinction of color. DufahyDufahy a man of courage and heart, who had shown in the

administration of his properties at Saint-Domingue an unequivocal sympathy for the

oppressed race, was one of the deputies appointed on this occasion.

Scarcely had the National Convention learned of the acts of PolverelPolverel and of SonthonaxSonthonax, its

commissioners with regard to everything concerning slaves, that it approved them;

their greatness was recognized. And immediately, to the applause of the immortal

assembly, was pronounced forthwith, at the request of Dufahy, not only the

emancipation of the entire black race, but also its reintegration into the great

national family.[33]

Thus was manifested, at the first appeal with regard to the blacks, the French

revolution's spirit of justice; and its project of the reintegration of the rights

of man, undertaken against all obstacles, seemed for a moment codified

forever.

It was in the month of February 1794, that the National Convention issued the

memorable decree which abolished slavery throughout the French

colonies; a decree believed to be forever irrevocable.

All that remained for the French Republic to do was to take pride in this most glorious measure, to which it proceeded with such a resolute spirit and with such firmness. Freedom

established itself in consequence, de facto and de jure, in

those of our colonies which England had not succeeded in seizing.

The emancipation of the blacks had the first result of preserving for France its

richest colony, Saint-Domingue. Once free, the blacks of Saint-Domingue, who it

would have been hardly surprising to see comport themselves differently upon

achieving liberty, gave striking proofs of their good will, and of their aptitude

for all kinds of work. Under this regenerative regime, the colony organized

itself, the workshops were all in activity, the crops flourished. This

state of affairs lasted, not without remarkable progress, until 1802, when

NapoleonNapoleon, misled by the fatality of his

illiberal ideas, tried to reestablish slavery where the National Convention had

made it disappear. We must see in Mr. Macaulay's excellent book on Haiti [34] the curious details of this emancipation, somewhat

improvised, of the black race in the most considerable of our colonial possessions

of that period. Mr. Macaulay's work is filled not only with unknown facts about

the war of independence in HaitiHaiti, but also with irrefutable evidence against the

errors propagated with the most flagrant bad faith by the enemies of the cause of

the blacks.

He triumphantly proves that the greatest disasters were the result of the return

to slavery in 1802, undertaken beyond all reason and all necessity by the First

Consul.

The French army, fighting for a bad cause, was defeated, and perished. The blacks

remained masters of the land, and laid there the foundations of the social state

which they enjoy today, a social state far superior to that of many supposedly

civilized European nations.[35] The problem of free labor in the

Antilles was thereby solved, and today the example of the emancipated English

colonies must have convinced even the most dimwitted of the falsity and infamy of

the assertions of the colonists against the blacks.[36]

That which was decreed by the National Convention in 1794, for the French

possessions, which was established by force of circumstance following the wars of

independence of Saint-Domingue, which has just been organized for the English

colonies, namely: the emancipation of the blacks and free labor, we claim it today

on the most legitimate grounds, in the name of principle and necessity, and we

want to establish it by reason and according to a law of justice and reparation,

without delay.[37]

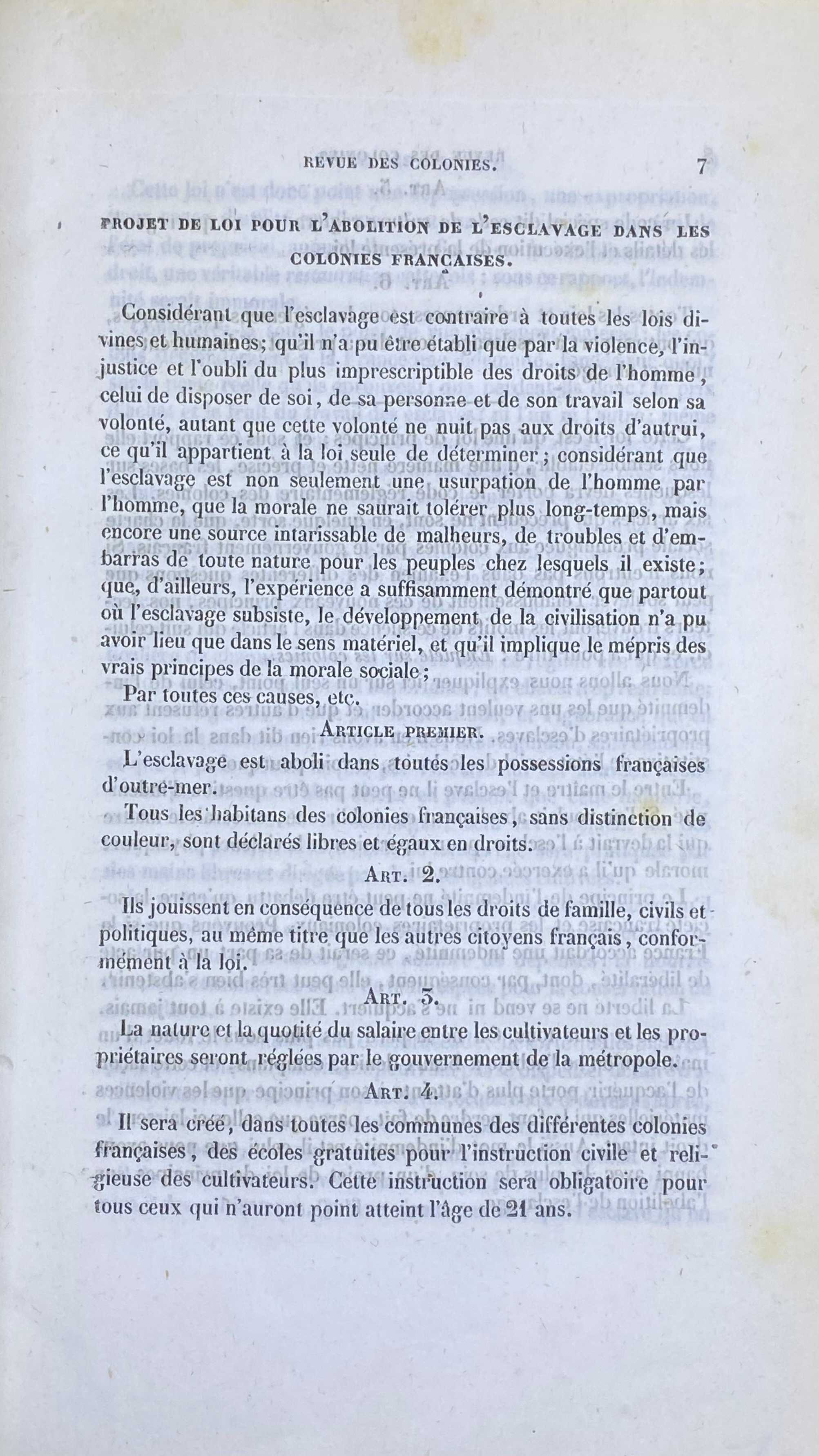

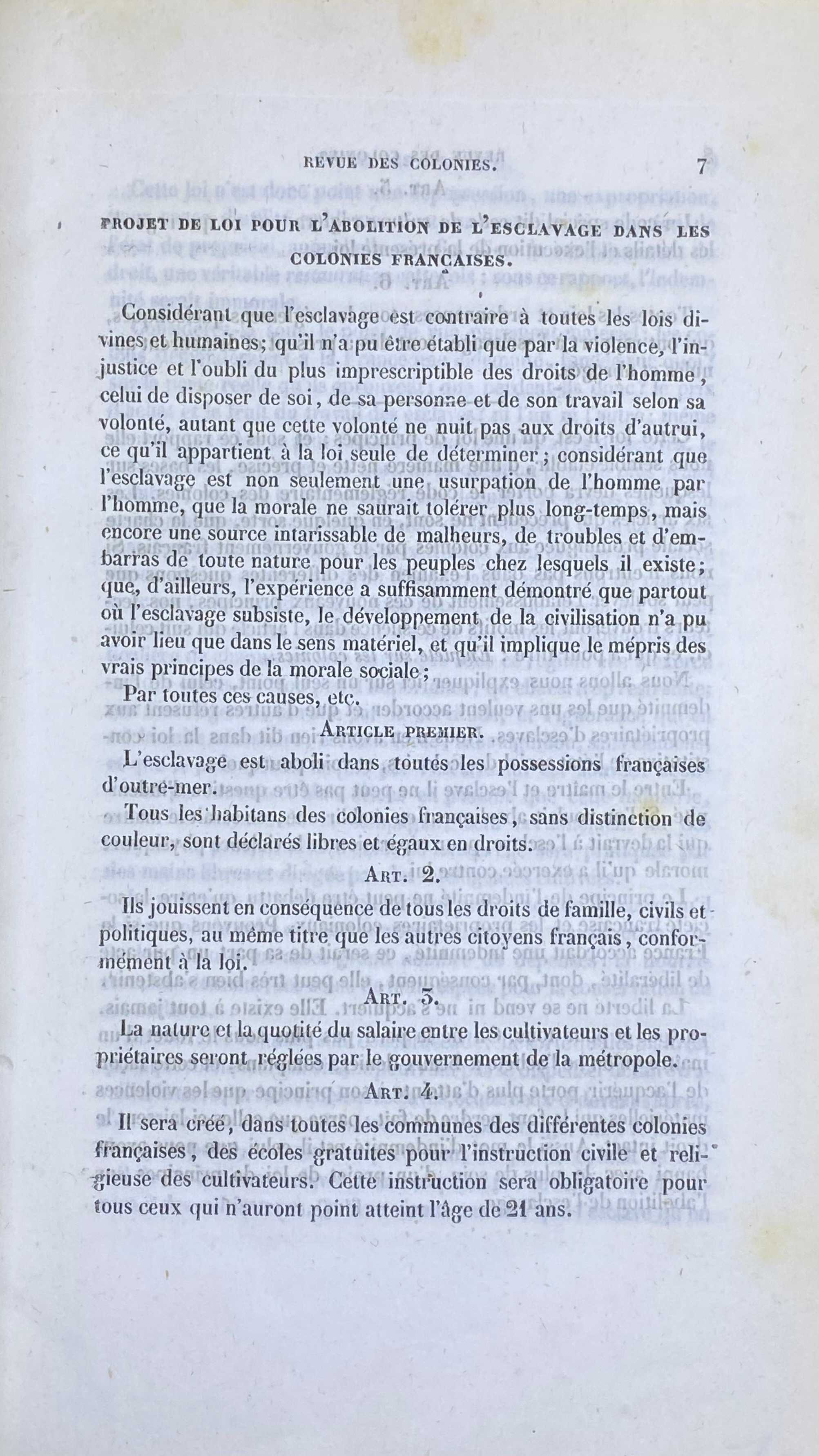

BILL FOR THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY IN THE FRENCH COLONIES.

Considering that slavery is contrary to all divine and human laws; that it could

only have been established through violence, injustice and contempt for the most

imprescriptible of human rights, the right to dispose of one's person and one's

work according to one's will, insofar as this will does not infringe upon the

rights of others, which it is for the law alone to determine; considering that

slavery is not only a usurpation of man by man, which can no longer be tolerated

morally, but furthermore an inexhaustible source of misfortunes, troubles, and

concerns of all kinds for the peoples whom it affects; that, moreover, experience

has sufficiently proven that wherever slavery persists, only material development

can take place, and that it implies contempt for the true principles of social

morality;

By all these causes, etc.

FIRST ARTICLE. Slavery is abolished in all French overseas

possessions.All the inhabitants of the French colonies, without distinction

of color, are declared free and equal in rights.[38]

ART. 2.They therefore enjoy all family, civil and political rights, in the

same way as other French citizens, in accordance with the law.

ART. 3.The nature and the quota of the wages between the laborers[39] and the landowners will be regulated by the government of the

metropole.

ART. 4 There will be created, in all the communes of the different French

colonies, free schools for the civil and religious instruction of the laborers.

This instruction will be compulsory for all those who have not reached the age of

21.[40]

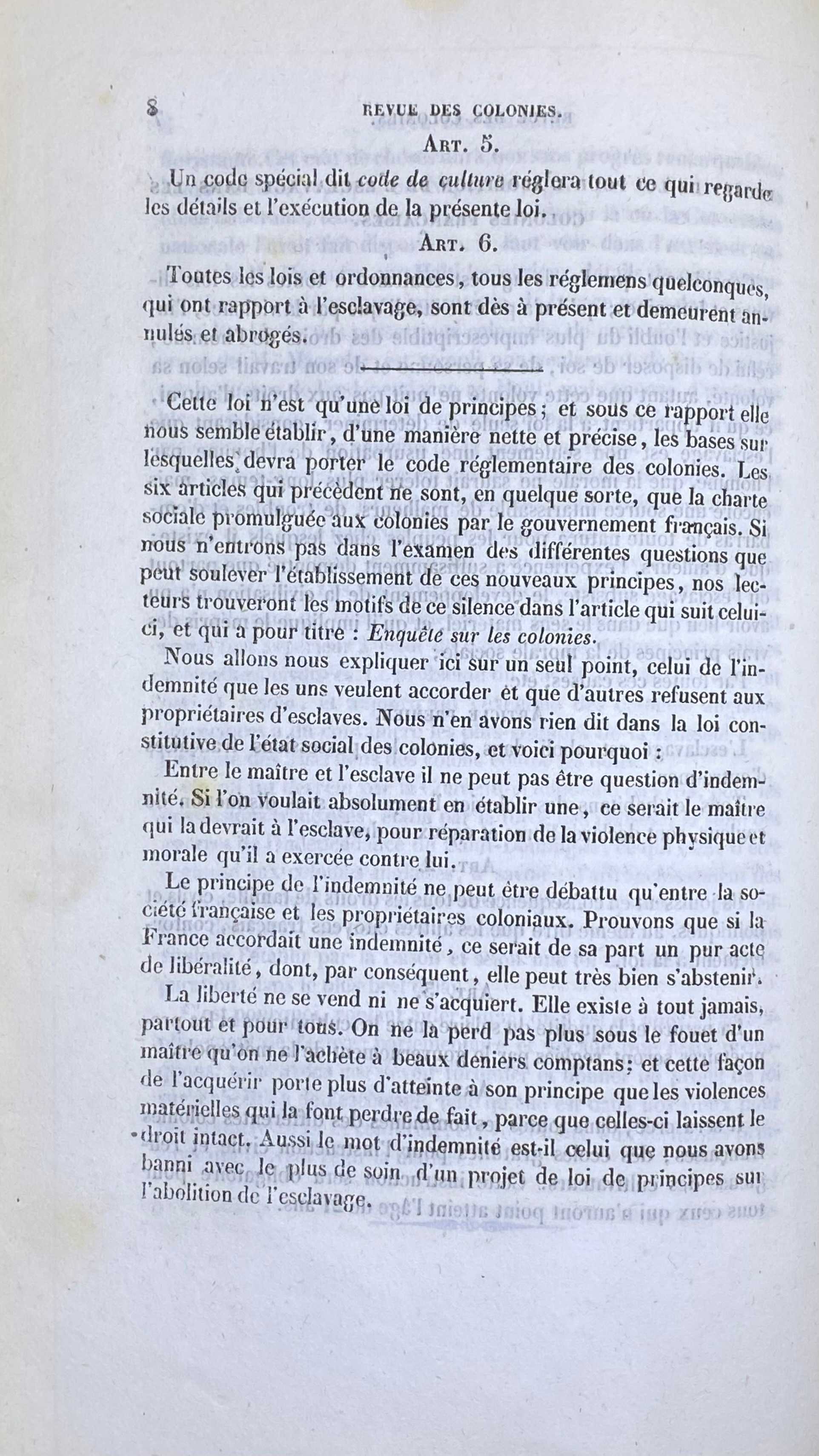

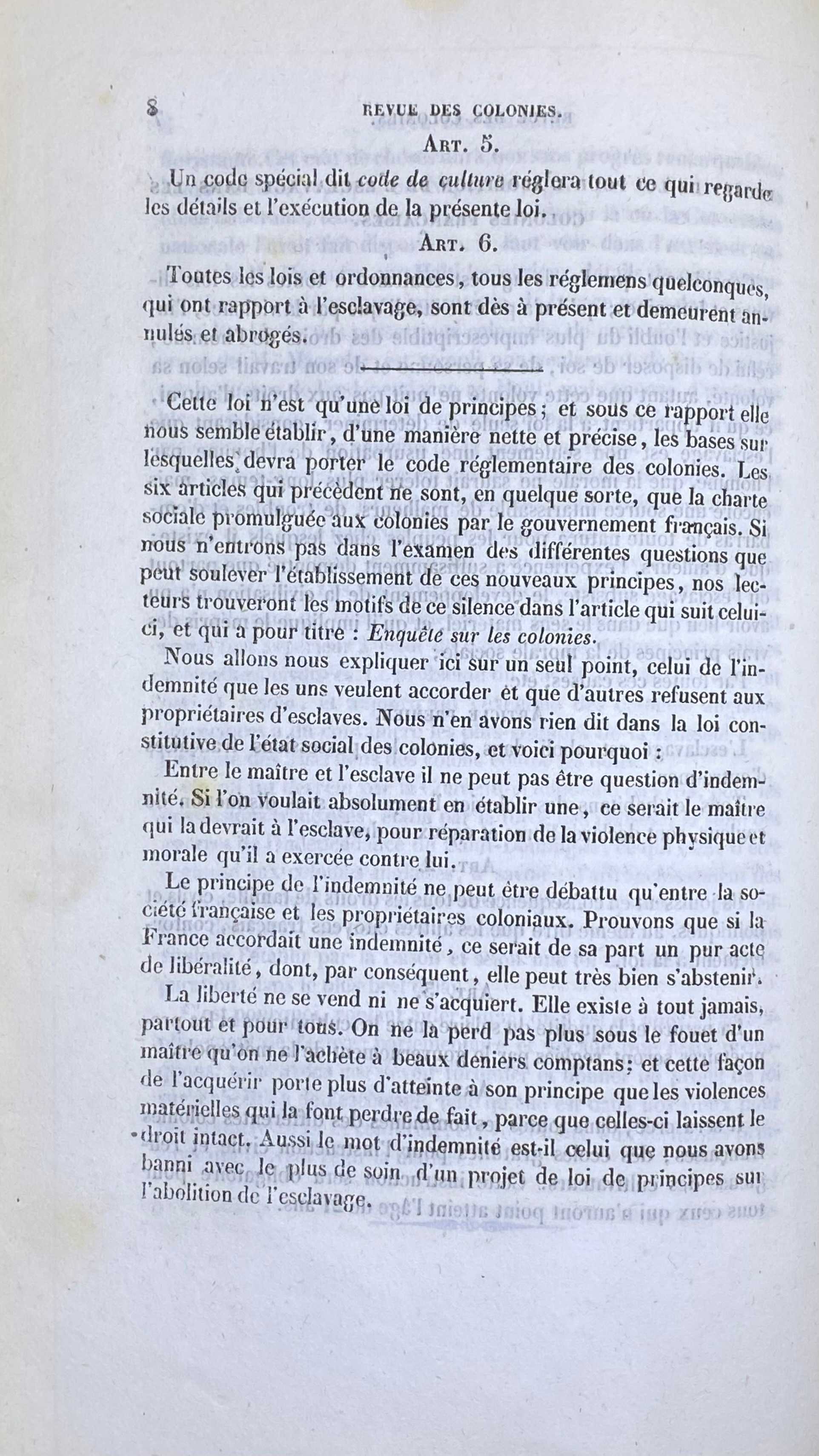

ART. 5. A special code called the code of culture will regulate all that

concerns the details and the execution of this law.

ART. 6. All laws and ordinances, all regulations whatever, which relate to

slavery, are from now on and remain annulled and abrogated.

This law is but a law of principles; and in this respect it seems to us to

establish, in a clear and precise manner, the bases on which the regulatory code

of the colonies will need to rest. The six articles that precede are, in a way,

only the social charter promulgated in the colonies by the French government. If

we do not enter into the examination of the various questions which the

establishment of these new principles may raise, our readers will find the reasons

for this silence in the article that follows this one, entitled: Inquiry

into the colonies.

We will explain ourselves here on only one point, that of the indemnity that some

want to grant and that others refuse to the owners of slaves. We have said nothing

about it in the law constituting the social state of the colonies, and here is

why:

Between the master and the slave there can be no question of indemnity.[41] If one absolutely wanted to establish one, it would be the

master who would owe it to the slave, as reparation for the physical and moral

violence he has exercised against him.[42]

The principle of indemnity can only be debated between French society and the

colonial landowners. Let us prove that if France granted an indemnity, it would

be, on its part, a pure act of liberality, from which, consequently, it would do

well to abstain.

Freedom is neither sold nor acquired. It exists forever, everywhere, and for

everyone. One no more loses it under the whip of a master than one buys it for

cold cash; and this way of acquiring it strikes more at its principle than the

material violence that causes it to be lost, in fact, because this, at least,

leaves the right intact. The word indemnity is, accordingly, the one which we have

most carefully banished from a bill of principles on the abolition of slavery.[43]

This law is therefore not a dispossession, an expropriation, for reasons of

public utility; on the contrary, it is the negation of the state of property, to

which it puts an end. It is the reestablishment of rights, a real restoration[44] this time: in this respect, the indemnity would be immoral.

Consider it from a purely material point of view; the colonists would ask France

for an indemnity, founded on what? on the actual loss they incur; what is it that

they are losing? the purchase price and the fruit of slave labor? Neither; even in

the hypothesis most favorable to the slave owners, the purchase price must be put

out of the question for the greatest number, since the slave trade has been

abolished for a long time, and that it would be unreasonable to found the demand

for justice upon the violation of the law. Moreover, the purchase price of a slave

is nothing more than a kind of import duty paid in order to be able to take

advantage of the labor of the imported commodity[45]. This work is the one and only profit generator of the masters. One should not

quantify the particular industry of each slave because under this mode it is

exerted too narrowly, too restricted; because intelligence, dulled by servitude,

and the ignorance which is its necessary consequence, is without force, without

guide, without direction, and because the small savings acquired by the slave are

often discarded to him by the master.[46] But let us say in passing that this

industry, besides the work in the fields, will certainly be one of the means of

prosperity of the colonies when it is practiced by free hands and directed by

cultivated intelligences.

The master therefore derives only one profit, either from the slave whom he buys,

or from the one who is born on his property: labor; and this profit imposes on him

a fairly large number of expenses: food, clothing, care of every kind for the

preservation of his slaves.

Well, the colonies are constituted in such a way that the masters, whatever their

rights may be, cannot dispense with having their former slaves work the land, and

that these, upon becoming free, will no less be laborers. The law changes, but the

fact will not, the master loses nothing; what the labor of his former slaves cost

him in overhead will be replaced by the wages he will give to them as free

laborers. Let him not come and say that the slave we removed from

under his dominion cost him 1500 and 2000 francs; for he has paid this price and

other expenses to profit from a labor that he may always obtain from the will of

the worker. Wages replace a great number of cares and expenses, and if, all things

considered, there is an increase, that is the fate of all modern industries.

Who does not see now that by compensating the former owners, the state would use

200 million to repair a chimerical evil. We have tried to leave the principles

aside for a moment, but if it were true that the dispossession of the master were

for him a material loss of money, that would not give him any more right to be

compensated; because there is no right against rights..

One will object, as a delegate in the tribune already has: “The blacks who have

become free will no longer work, the landowners will lose, the blacks will gain

nothing, the colonies will perish; all this with no advantage to anyone.” Error!

societies do not perish; they transform; blacks will work as laborers, and for two

reasons: so as not to starve, and in the hopes of obtaining a piece of land. They

will work better than before, and their crops, improved in the interest of the

landowners, would enable the farmers and workmen to successfully practice the

exercise of their industrial imaginations. Observe, moreover, that in all that

relates to the colonies, we always ask for an arbiter, France. We conceive nothing

without this moderating power; for, indeed, we do not dispute the difficulties

which the transition from the old to the new state produced by the abolition of

slavery may present; but that is no reason to adjourn the question

indefinitely.[47]

With the help of the French government, the colonies can reform themselves and

live without harm to any portion of their inhabitants. Without this intervention,

they will certainly not perish as human societies, but they will perish as

European societies. There would come a day when an inevitable, terrible struggle

would begin, and where force would determine the law. One must not think that, in

closing one's eyes, that which offends the gaze disappears, and that facts cease

to exist simply because one does not speak of them. The intermediary race of the

colonies is the necessary link between the old and the new order, the keystone of

the new social edifice.[48] Building on a legal basis, reforming

without violence, repairing without damage, such is our aim. It can be

accomplished under the patronage of France, and what's more, it can only be

accomplished with the aid of France.

Charter of 1814

Charte de 1814

The Charter of 1814 was the written constitution of the Restoration government. The Bourbon Monarchy’s return under Louis XVIII was not a return to absolutism, but rather a constitutional monarchy with an elected legislature in the lower house of parliament (suffrage was highly restricted) and appointed nobles in the upper house. Other aspects of the revolution remained, including civil liberties, religious tolerance, the administrative organization of the state, among others.

Müssig, Ulrike, “La Concentration monarchique du pouvoir et la diffusion des modèles constitutionnels français en Europe après 1800,” Revue Historique de Droit Français et Étranger 88, no. 2 (2010). 295–310. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43852557.

Stovall, Tyler, Transnational France: The Modern History of A Universal Nation . Avalon, 2015.

La Charte de 1814 est le texte constitutionnel du régime de la Restauration. Avec le retour des Bourbons sous Louis XVIII, la monarchie absolue ne renaît pas pour autant : elle devient une monarchie constitutionnelle. Le parlement se compose d’une chambre basse élue (avec un suffrage très restreint) et d’une chambre haute formée de nobles nommés. Certains acquis de la Révolution sont préservés, notamment les libertés civiles, la tolérance religieuse et l’organisation administrative de l’État.

Müssig, Ulrike, “La Concentration monarchique du pouvoir et la diffusion des modèles constitutionnels français en Europe après 1800,” Revue Historique de Droit Français et Étranger 88, no. 2 (2010). 295–310. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43852557.

Stovall, Tyler, Transnational France: The Modern History of A Universal Nation . Avalon, 2015.

Ordinance of 1825

Ordonnance de 1825

One of the Haiti’s main goals after independence, aside from preventing French reinvasion, was securing its economic well-being through formal recognition from the foreign governments it traded with. Negotiations for recognition failed under Dessalines, Pétion and Christophe, as various early independence governments balked at France’s terms and French agents’ continued designs on the land they continue to refer to under the colonial name of Saint-Domingue. President Jean-Pierre Boyer (1818–1843) attempted his own negotiations with France but his hand was ultimately forced when Charles X’s emissary, Baron Mackau, arrived with a military squadron in the harbor of Port-au-Prince with a new ordonnance from the king (dated April 17, 1825). The order stated that Haiti would give France preferential trade status via a reduced customs duty and pay a staggering 150 million francs to compensate French property owners for their “loss.” Boyer signed, under the threat of gunboats, on July 11, 1825.

Boyer’s government immediately took out a loan to make their first payment—borrowing 30 million francs from French banks in order to repay the French government for recognition of their independence. The indemnity agreement and the loans had disastrous consequences for the economic and political autonomy of the nation. Economists have estimated the total cost of the indemnity to Haiti over the last 200 years to be at least $21 billion dollars, perhaps as much as $115 billion.

https://memoire-esclavage.org/lordonnance-de-charles-x-sur-lindemnite-dhaitihttps://memoire-esclavage.org/lordonnance-de-charles-x-sur-lindemnite-dhaiti

https://esclavage-indemnites.fr/public/Base/1https://esclavage-indemnites.fr/public/Base/1

Blancpain, François, Un siècle de relations financières entre Haïti et la France (1825-1922) . L’Harmattan, 2001.

Brière, Jean-François, “L'Emprunt de 1825 dans la dette de l'indépendance haïtienne envers la France,” Journal of Haitian Studies 12, no. 2 (2006). 126–34.

Daut, Marlene, “When France Extorted Haiti—The Greatest Heist in History,” The Conversation , June 30, 2020, https://theconversation.com/when-france-extorted-haiti-the-greatest-heist-in-history-137949https://theconversation.com/when-france-extorted-haiti-the-greatest-heist-in-history-137949

Dorigny, Marcel; Bruffaerts, Jean-Claude; Gaillard, Gusti-Klara; and Théodat, Jean-Marie, eds., Haïti-France. Les chaînes de la dette. Le rapport Mackau (1825) . Hémisphères Éditions, 2022.

Gaffield, Julia, “The Racialization of International Law after the Haitian Revolution: The Holy See and National Sovereignty,” The American Historical Review 125, no. 3 (2020). 841–868. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhz1226

Porter, Catherine; Méhout, Constan; Apuzzo, Matt; and Gebrekidan, Selam, “The Ransom,” The New York Times , 20 Mai 2022.

L’un des principaux objectifs d’Haïti après son indépendance, en plus de prévenir une éventuelle réinvasion française, est d’assurer sa stabilité économique en obtenant une reconnaissance officielle des gouvernements étrangers avec lesquels elle commerce. Sous Dessalines, Pétion et Christophe, les négociations en ce sens échouent, les premiers gouvernements haïtiens refusant d’accepter les conditions imposées par la France, tandis que les agents français continuent à revendiquer le territoire sous son nom colonial de Saint-Domingue.

Le président Jean-Pierre Boyer (1818–1843) entreprend à son tour des négociations avec la France, mais la situation prend un tournant décisif lorsque l’émissaire de Charles X, le baron Mackau, arrive dans le port de Port-au-Prince à la tête d’une escadre militaire, porteur d’une ordonnance royale datée du 17 avril 1825. Celle-ci stipule qu’Haïti doit accorder à la France un statut commercial préférentiel, par le biais d’une réduction des droits de douane, et verser une indemnité de 150 millions de francs pour compenser les propriétaires français de la « perte » de leurs biens. Sous la pression militaire, Boyer signe l’accord le 11 juillet 1825.

Afin de s’acquitter du premier paiement, son gouvernement contracte immédiatement un emprunt de 30 millions de francs auprès de banques françaises, destiné à financer la somme exigée par le gouvernement français en échange de la reconnaissance officielle de l’indépendance haïtienne. L'accord d'indemnité et les emprunts contractés ont des conséquences désastreuses sur l'autonomie économique et politique de la nation. Les économistes estiment que le coût total de l'indemnité pour Haïti au cours des 200 dernières années s'élève à au moins 21 milliards de dollars (environ 19,11 milliards d'euros), voire jusqu'à 115 milliards de dollars (environ 104,65 milliards d'euros).

Blancpain, François, Un siècle de relations financières entre Haïti et la France (1825-1922) . L’Harmattan, 2001.

Brière, Jean-François, “L'Emprunt de 1825 dans la dette de l'indépendance haïtienne envers la France,” Journal of Haitian Studies 12, no. 2 (2006). 126–34.

Daut, Marlene, “When France Extorted Haiti—The Greatest Heist in History,” The Conversation , 30 Juin 2020, https://theconversation.com/when-france-extorted-haiti-the-greatest-heist-in-history-137949https://theconversation.com/when-france-extorted-haiti-the-greatest-heist-in-history-137949

Dorigny, Marcel; Bruffaerts, Jean-Claude; Gaillard, Gusti-Klara; et Théodat, Jean-Marie, eds., Haïti-France. Les chaînes de la dette. Le rapport Mackau (1825) . Hémisphères Éditions, 2022.

Gaffield, Julia, “The Racialization of International Law after the Haitian Revolution: The Holy See and National Sovereignty,” The American Historical Review 125, no. 3 (2020). 841–868. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhz1226

Porter, Catherine; Méhout, Constan; Apuzzo, Matt; and Gebrekidan, Selam, “The Ransom,” The New York Times , May 20, 2022.

Law of Floréal, Year 10

Loi de floréal, an 10

The loi de floréal an 10 refers to the decree-law (or statuary law) authorizing the slave trade and slavery in the colonies restored by the Treaty of Amiens (Décret-loi autorisant la traite et l'esclavage dans les colonies restituées par le traité d’Amiens). The law, proposed by First Consul Bonaparte and debated by the assemblies, was adopted on May 20, 1802 (30 floréal an 10).

The pertinent text of the law is as follows:

Article 1: “Dans les colonies restituées à la France en exécution du traité d’Amiens, du 6 germinal an X, l’esclavage sera maintenu conformément aux lois et réglemens antérieures à 1789.”Article 3: “La traite des noirs et leur importation des lesdites colonies, auront lieu, conformément aux lois et règlemens existans avant ladite époque de 1789.”

Slavery had been abolished first in Saint Domingue in 1793 by civil commissioners Leger-Félicité Sonthonax and Étienne Polverel. A committee from Saint-Domingue then sailed to France to urge the government to ratify the 1793 proclamations for all French colonies. On February 4, 1794 the Convention proclaimed slavery abolished throughout the Republic. Though applied in Guadeloupe and, eventually, Guyana, the 1794 decree was not applied in Martinique, Saint Lucia or Tobago (then under British occupation) or in the Indian Ocean colonies (which essentially delayed and refused). The Treaty of Amiens signed March 15, 1802 with Great Britain thus restored to France those colonies that had maintained slavery and the slave trade throughout the period of occupation. The May 20 law did not reestablish slavery throughout the French colonies but was nevertheless a stark retreat from the values of 1789: slavery and the slave trade was now legal in the French Republic. A consular order from July 16, 1802 (27 messidor an X) reestablished slavery in Guadeloupe.

There is a lack of clarity, both in contemporary scholarship and in the Revue, on the nature of the May 20 decree-law. Scholars often incorrectly cite the law as the date that marks Bonaparte’s reestablishment of slavery throughout the French colonies. Bissette’s exaggerated claim, “Tout le monde sait que la loi de floréal an 10, qui rétablit l’esclavage dans les colonies, fut le signal de la défection de tous les chefs de Saint-Domingue” reveals that this confusion was in place even in 1830s. It also confirms the effectiveness of Bonaparte’s attempts to reestablish slavery under the radar and without fanfare. Nevertheless, Bissette is correct about the consequences of Bonaparte and the Consulate’s pro-slavery machinations in contributing to the anticolonial, antislavery act of Haitian independence.

Niort, Jean-François and Richard, Jérémie, “ A propos de la découverte de l’arrêté consulaire du 16 juillet 1802 et du rétablissement de l’ancien ordre colonial (spécialement de l’esclavage) à la Guadeloupe,” Bulletin de la Société d’Histoire de la Guadeloupe no. 152 (2009). 31–59. https://doi.org/10.7202/1036868ar

Bénot, Yves and Dorigny, Marcel, eds., Rétablissement de l’esclavage dans les colonies françaises. Aux origines de Haïti . Maisonneuve et Larose, 2003.

La loi de floréal an 10 désigne le décret rétablissant officiellement la traite et l’esclavage dans les colonies restituées à la France par le traité d’Amiens. Proposée par le Premier Consul Bonaparte et débattue par les assemblées, elle fut adoptée le 20 mai 1802 (30 floréal an 10).

Les articles les plus significatifs en sont les suivants :

Article 1 : « Dans les colonies restituées à la France en exécution du traité d’Amiens, du 6 germinal an X, l’esclavage sera maintenu conformément aux lois et réglemens antérieurs à 1789. »

Article 3 : « La traite des Noirs et leur importation dans lesdites colonies auront lieu, conformément aux lois et réglemens existants avant ladite époque de 1789. »

L’abolition de l’esclavage avait été proclamée pour la première fois à Saint-Domingue en 1793 par les commissaires civils Léger-Félicité Sonthonax et Étienne Polverel. Un comité mandaté par la colonie s’était alors rendu en France pour plaider en faveur d’une généralisation de cette mesure. Le 4 février 1794, la Convention nationale décréta l’abolition de l’esclavage dans l’ensemble de la République. Ce décret fut appliqué en Guadeloupe et, plus tard, en Guyane, mais resta sans effet en Martinique, à Sainte-Lucie et à Tobago, alors sous occupation britannique, ainsi que dans les colonies de l’océan Indien, où son application fut délibérément différée.

Le traité d’Amiens, signé avec la Grande-Bretagne le 15 mars 1802, permit à la France de récupérer plusieurs colonies où l’esclavage et la traite avaient été maintenus sous administration britannique. La loi du 20 mai 1802 ne rétablissait pas formellement l’esclavage dans l’ensemble des territoires français, mais elle marquait une rupture avec les principes de 1789 en entérinant la légalité de l’esclavage et de la traite dans certaines colonies. Quelques mois plus tard, un arrêté consulaire du 16 juillet 1802 (27 messidor an X) confirma explicitement le rétablissement de l’esclavage en Guadeloupe.

Tant l’historiographie contemporaine que la Revue des Colonies entretiennent une certaine confusion quant à la portée exacte du décret du 20 mai. Nombre d’historiens citent à tort cette loi comme l’acte fondateur du rétablissement de l’esclavage dans toutes les colonies françaises. L’affirmation de Cyrille Bissette—« Tout le monde sait que la loi de floréal an 10, qui rétablit l’esclavage dans les colonies, fut le signal de la défection de tous les chefs de Saint-Domingue »—illustre bien que cette lecture erronée existait déjà dans les années 1830. Elle témoigne également du succès de la stratégie de Bonaparte, qui chercha à rétablir l’esclavage de manière discrète, sans déclaration officielle retentissante. Pourtant, Bissette ne se trompe pas sur les effets des politiques du Consulat : les manœuvres pro-esclavagistes de Bonaparte contribuèrent directement à l’acte d’indépendance haïtien, dont la portée fut à la fois anticoloniale et antiesclavagiste.

https://memoire-esclavage.org/napoleon-et-le-retablissement-de-lesclavage/lessentiel-dossier-napoleon-et-le-retablissement-de

https://www.portail-esclavage-reunion.fr/documentaires/abolition-de-l-esclavage/l-abolition-de-l-esclavage-a-la-reunion/la-premiere-abolition-de-lesclavage-par-la-france-et-sa-non-application-a-la-reunion/

Niort, Jean-François et Richard, Jérémie, “ A propos de la découverte de l’arrêté consulaire du 16 juillet 1802 et du rétablissement de l’ancien ordre colonial (spécialement de l’esclavage) à la Guadeloupe,” Bulletin de la Société d’Histoire de la Guadeloupe no. 152 (2009). 31–59. https://doi.org/10.7202/1036868ar

Bénot, Yves et Dorigny, Marcel, eds., Rétablissement de l’esclavage dans les colonies françaises. Aux origines de Haïti . Maisonneuve et Larose, 2003.

Revue Coloniale

Revue Coloniale

The Revue Coloniale, was an ephemeral monthly periodical, printed in Paris during the year 1838. Its founder Édouard Bouvet and editor Rosemond Beauvallon conceived of it on the model of many similar, contemporaneous publications reporting on political and economic questions of interest to white colonists while also attending to arts and literature, as attested by the journal’s complete title: Revue Coloniale. intérêts des colons : marine, commerce, littérature, beaux-arts, théâtres, modes. In the December 1838 issue of the Revue des Colonies, Cyrille Bissette acknowledges the Revue Coloniale as both an ideological opponent and a competitor in the print market.

Fondée par Édouard Bouvet et dirigée par Rosemond Beauvallon, la Revue Coloniale, sous-titrée intérêts des colons : marine, commerce, littérature, beaux-arts, théâtres, modes, souscrit au modèle des revues destinées aux propriétaires coloniaux, rendant compte de l'actualité politique et économique des colonies tout en ménageant une place aux contenus littéraires, culturels et mondains. Dans le numéro de décembre 1838 de la Revue des Colonies, Cyrille Bissette reconnaît en la Revue Coloniale tant un adversaire idéologique qu'un concurrent dans le paysage médiatique.

Le Moniteur universel

Le Moniteur universel

Le Moniteur universel, often simply referred to as the “Le Moniteur” is one of the most frequently referenced nineteenth-century French newspapers. An important cultural signifier, it was referenced frequently in other publications, in fiction, and likely in contemporary discussions. Its title, derived from the verb monere, meaning to warn or advise, gestures at Enlightenment and Revolutionary ideals of intelligent counsel.

Initially, Le Moniteur universel was merely a subtitle of the Gazette Nationale, established in 1789 by Charles-Joseph Panckouke, who also published Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie. Only in 1811 that the subtitle officially ascended to title.

The Moniteur had become the official voice of the consular government in 1799. Under the Empire, it gained the privilege of publishing government acts and official communications, effectively becoming the Empire's primary propaganda outlet. However, its role was not confined to this function. It survived various political regimes, including the Revolution and the death of Panckouke in 1798. Its longevity can be attributed to its adaptability, with its successive iterations reflecting the political culture of each historical stage, transitioning from an encyclopedic model during the Revolution, to a state propaganda tool during the First Empire, to a collection of political speeches under the constitutional monarchy and the Second Republic, and finally, to a daily opinion newspaper for the general public under Napoleon III.

During the print run of the Revue des Colonies, the “Moniteur” was divided into two main sections: the “official” and the “unofficial” part. Government documents and official communications were published in the official section, while other current events and various topics were featured in the unofficial section under a range of headings such as “Domestic,” “International,” “Entertainment,” etc. The texts cited in Revue des Colonies were most often found in the unofficial section, typically under the “Domestic” heading and on the front page.

Titles containing the label “Moniteur” followed by a toponym abounded throughout the nineteenth century: local or colonial titles used this formula to emphasize their official status, maintaining the distinction between the official and unofficial sections.

Laurence Guellec, « Les journaux officiels », La Civilisation du journal (dir. Dominique Kalifa, Philippe Régnier, Marie-Ève Thérenty, Alain Vaillant), Paris, Nouveau Monde, 2011. https://www.retronews.fr/titre-de-presse/gazette-nationale-ou-le-moniteur-universelhttps://www.retronews.fr/titre-de-presse/gazette-nationale-ou-le-moniteur-universel .

Le Moniteur universel, ou « Le Moniteur », est l’un des journaux les plus cités, sous cette forme abrégée et familière, au cours du XIXe siècle : on le retrouve, véritable élément de civilisation, dans la presse, dans les fictions, probablement dans les discussions d’alors. Ce titre, qui renvoie au langage des Lumières et de la Révolution, dérive étymologiquement du verbe monere, signifiant avertir ou conseiller. Il n’est d’abord que le sous-titre de la Gazette nationale, créée en 1789 par Charles-Joseph Panckouke, éditeur entre autres de l’Encyclopédie de Diderot et d’Alembert ; ce n’est qu’en 1811 que le sous-titre, Le Moniteur universel, devient officiellement titre.

Lancé en 1789, ce périodique devient en 1799 l’organe officiel du gouvernement consulaire ; il obtient ensuite, sous l’Empire, le privilège de la publication des actes du gouvernement et des communications officielles, passant de fait au statut d’« organe de propagande cardinal de l’Empire ». Il ne se limite pourtant pas à cette fonction, et survit aux différents régimes politiques comme il a survécu à la Révolution et à la mort de Panckouke en 1798. Sa survie est notamment liée à sa capacité à changer : les modèles adoptés par sa rédaction, qu'ils soient choisis ou imposés par le pouvoir en place, reflètent de manière révélatrice la culture politique propre à chaque période marquante de son histoire. Ainsi, comme le souligne Laurence Guellec, il se transforme en une grande encyclopédie pendant la Révolution, devient un instrument de propagande étatique sous le Premier Empire, se mue en recueil des discours des orateurs durant la monarchie constitutionnelle et la Seconde République, puis se positionne en tant que quotidien grand public et journal d'opinion sous le règne de Napoléon III. Ajoutons enfin que les titres constitués du syntagme « Moniteur » suivi d’un toponyme sont nombreux, au cours du siècle, en France : les titres locaux ou coloniaux adoptent cette formule pour mettre en exergue leur ancrage officiel, et respectent la distinction entre partie officielle et non officielle.

À l’époque de la Revue des Colonies, Le Moniteur universel est organisé en deux grandes parties : la « partie officielle » et la « partie non officielle ». Les actes du gouvernement et les communications officielles, quand il y en a, sont publiés dans la partie officielle, en une – mais parfois en quelques lignes – et les autres textes, tous d’actualité mais aux thèmes divers, paraissent dans la partie non officielle sous des rubriques elles aussi variées : intérieur, nouvelles extérieures, spectacles, etc. Les textes que cite la Revue des Colonies paraissent dans la partie non officielle, le plus souvent sous la rubrique « Intérieur » et en une.

Laurence Guellec, « Les journaux officiels », La Civilisation du journal (dir. Dominique Kalifa, Philippe Régnier, Marie-Ève Thérenty, Alain Vaillant), Paris, Nouveau Monde, 2011. https://www.retronews.fr/titre-de-presse/gazette-nationale-ou-le-moniteur-universelhttps://www.retronews.fr/titre-de-presse/gazette-nationale-ou-le-moniteur-universel .