Revue des Colonies V.1 N°1 (selection in English translation)

Maria Beliaeva Solomon

Annotated by

A. Lagarde

M. Beliaeva Solomon

A. Louis

A. Brickhouse

Charlotte Joublot Ferré

C. Stieber

E. Hautemont

G. Pierrot

J. Couti

J. Balguy

K. Duke-Bryant

L. Demougin

M. L. Daut

M. Roy

N. Romney

S. E. Johnson

T. Tirkawi

Y. Najm

Publication Information

Information about the source

REVUEDESCOLONIES,

MONTHLY COMPENDIUM[1] OF POLITICS,

ADMINISTRATION, JUSTICE, INSTRUCTION AND COLONIAL CUSTOMS,

BY A SOCIETY OF MEN OF COLORSOCIETY OF MEN OF COLOR

DIRECTED BY C.-A. BISSETTEC.-A. BISSETTE.

N°1July.

PARIS, AT THE OFFICE OF THE

REVUE DES COLONIES,46, RUE NEUVE-SAINT-EUSTACHE

1834.

REVUEDES COLONIES

Prospectus.

As of now, the colonies, generally speaking, only know of the great

principles of philanthropy in theory; of freedom in action, nothing at all.

The suffering and oppressed classes appeal and fight relentlessly, always in

vain. To stimulate the feeble good will to which our rulers limit

themselves, it is necessary to compile the just complaints that arise from

all sides. These claims, these grievances, to be successful, must receive

the greatest publicity: this is the object of our RevueRevue

The debate floor today is no longer enough; petitions are

adjourned by the calculated negligence of rapporteurs or pushed back by the

insolent agendas of the day. On the other hand, colonial authorities, always

disposed in favor of the privileged, cleverly evade the ministers'

prescriptions. Against this hitherto successful tactic of the partisans of

aristocracy and privilege, it is necessary to finally engage the power of

public opinion, enlightened by a discussion always wise, always true, but

energetic and never timid, of the causes, whatever they may be, which hinder

the desirable fusion of the diverse populations of the colonies.[2]

For this purpose, a specialized journal is founded under the title of Revue des Colonies Revue des Colonies,

with Mr. BissetteMr. Bissette as director.

This journal is not only dedicated to all that concerns the colonies,

considered as a source of news and interesting facts apt to occupy the

leisure of the reader, but it devotes itself entirely to the political,

intellectual, moral and industrial interests of colonists of either

color.[3]

Nothing that concerns the French colonies in particular will be omitted from

this monthly publication. The government, the administration, and the

justice system will be examined here with respect to both their actions and

their persons; for it is the latter that too often determines the spirit and

the manner in which populations are either oppressed or well looked

after.

The civil, political, and social rights of the two free classes, which,

having been hitherto divided, ought to be united, will here be advanced and

supported with indefatigable zeal.

The great question of the abolition of slavery, the cornerstone of liberty,

will here be treated with the most conscientious care and the most ardent

love of equality and of the general good.[4]

Arbitrariness and partiality will here be brought to face the court of public

opinion with no distinction between persons. The weak will find here support

and protection, the oppressor, punishment, the official, warranted blame for

his illegal acts, but respect for his person.

The Revue des ColoniesRevue des Colonies will also concern itself with all the

changes made or projected in the legislation that governs foreign colonies

and inevitably affects our own in a powerful way.[5]

National interests, in relation to the possession of AlgiersAlgiers, will find in the Revue des ColoniesRevue des Colonies

a devoted and independent outlet.[6]

Numerous and knowledgeable correspondents ensure that readers find as much

variety as edification in the articles of the Revue des

Colonies.Revue des

Colonies.

DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLES.

The Revue des ColoniesRevue des Colonies believes it must, above all, indicate

by what principles it will offer judgment upon men and things.[7] In its estimation, '89, in the immortal Declaration of

Rights voted by the National AssemblyNational Assembly, laid the

future foundations of all truly democratic institutions; this is why we

inscribe this Declaration at the beginning of this

compendium: these are the tables of our law.

The rights of men had been misunderstood, insulted for centuries;

they have been restored for all mankind by this

Declaration, which will forever remain a rallying

cry against oppressors, and a law for legislators themselves.

(Address of the National AssemblyNational Assembly

to the French People, 11 February 1790.)

Excerpt

FROM THE MINUTES OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLYNATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF AUGUST

20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26 AND OCTOBER 1st, 1789.

DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS OF MAN IN SOCIETY.[8]

The representatives of the French People, formed into a National

Assembly, considering ignorance, forgetfulness or contempt of the rights

of man to be the only causes of public misfortunes and the corruption of

Governments, have resolved to set forth, in a solemn Declaration, the

natural, unalienable and sacred rights of man, to the end that this

Declaration, constantly present to all members of the body politic, may

remind them unceasingly of their rights and their duties; to the end

that the acts of the legislative power and those of the executive power,

since they may be continually compared with the aim of every political

institution, may thereby be the more respected; to the end that the

demands of the citizens, founded henceforth on simple and incontestable

principles, may always be directed toward the maintenance of the

Constitution and the happiness of all.

In consequence whereof, the National Assembly recognizes and declares,

in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the

following Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

Article 1.-Men are born and remain free and equal in

rights. Social distinctions may be based only on considerations of the

common good.

2.- The aim of every political association is the preservation of the

natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are Liberty,

Property, Safety and Resistance to Oppression.

3.-The source of all sovereignty lies essentially in the

Nation. No corporate body, no individual may exercise any authority that

does not expressly emanate from it.

4.- Liberty consists in being able to do anything that does not harm

others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of every man has no

bounds other than those that ensure to the other members of society the

enjoyment of these same rights. These bounds may be determined only by

Law.

5.- The Law has the right to forbid only

those actions that are injurious to society. Nothing that is not

forbidden by Law may be hindered, and no one may be compelled to do what

the Law does not ordain.

5.-

6.-

The Law is the expression of the general will. All citizens

have the right to take part, personally or through their

representatives, in its making. It must be the same for all, whether it

protects or punishes. All citizens, being equal in its eyes, shall be

equally eligible to all high offices, public positions and employments,

according to their ability, and without other distinction than that of

their virtues and talents.

7.- No man may be accused, arrested or detained except in the cases

determined by the Law, and following the procedure that it has

prescribed. Those who solicit, expedite, carry out, or cause to be

carried out arbitrary orders must be punished; but any citizen summoned

or apprehended by virtue of the Law, must give instant obedience;

resistance makes him guilty.

8.- The Law must prescribe only the punishments that are strictly and

evidently necessary; and no one may be punished except by virtue of a

Law drawn up and promulgated before the offense is committed, and

legally applied.

9.- As every man is presumed innocent until he has been declared guilty, if it should be considered

necessary to arrest him, any undue harshness that is not required to

secure his person must be severely curbed by Law.

10. - No one may be disturbed on account of his opinions, even religious

ones, as long as the manifestation of such opinions does not interfere

with the established Law and Order.

11.- The free communication of ideas and of opinions is one of the most

precious rights of man. Any citizen may therefore speak, write and

publish freely, except what is tantamount to the abuse of this liberty

in the cases determined by Law.

12.- To guarantee the Rights of Man and of the Citizen a public force is

necessary; this force is therefore established for the benefit of all,

and not for the particular use of those to whom it is entrusted.

13. For the maintenance of the public force, and for administrative

expenses, a general tax is indispensable; it must be equally distributed

among all citizens, in proportion to their ability to pay.

14. All citizens have the right to ascertain, by themselves, or through

their representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it

freely, to watch over its use, and to determine its proportion, basis,

collection and duration.

15. Society has the right to ask a public official for an accounting of

his administration.

16. Any society in which no provision is made for guaranteeing rights or

for the separation of powers, has no Constitution.

17.- Since the right to Property is inviolable and sacred,

no one may be deprived thereof, unless public necessity, legally

ascertained, obviously requires it, and just and prior indemnity has

been paid.

Excerpt from the minutes of the National

AssemblyNational

Assembly, October 1, 1789. Collated true to the

original. Signed MOUNIER, president; Viscount DE MIRABEAU,

DEMEUNIER, BUREAU DE Pusy, Bishop DE NANCY, FAYDEL, Abbot of EYMAR,

secretaries.

All of the principles of '89 are in this declaration; and, whatever one does,

there is in these principles, which the French revolution, by its republican

and imperial armies, has sown acrossed the land of

Europe, and by its books everywhere in the

universe, a power which cannot be suppressed.

Certainly, if a man should be reminded of anything, it is his rights, which

aristocracies may well succeed in making obsolete here and there, but to

which the future belongs.

We ask that we compare the present state of our legislation with this page of

justice and liberty, that we examine whether the laws that are made for us

are in conformity with the principles of this declaration, which must be

forever, according to the fine expression of the National

AssemblyNational

Assembly, the law of the legislators themselves.

And if this examination clearly shows that the government, whatever it may

be, is not founded on this one equitable basis — the enforcement of the

rights of all — those who, like us and with the National

AssemblyNational

Assembly, will be convinced that ignorance,

forgetfulness or contempt for the rights of man are the only causes of

public misfortunes and the corruption of governments, will

triumphantly conclude that all the evil of the present situation, in the

colonies as everywhere, is absolutely a result of this ignorance, of this

forgetfulness or of this contempt, we cannot precisely say which, as much on

the part of the rulers as on that of the governed.

The director, BISSETTEBISSETTE.

A LOOK AT THE COLONIAL REGIME AND ITS EFFECTS.

The deplorable events of Grand'Anse, [9]

MartiniqueMartinique have echoed through every

newspaper. Some, inspired by the authorities, in whose eyes all that is

emancipation becomes an object of terror, have presented this affair in an

unfavorable light to those who have limited themselves to passive

resistance.[10] Others, more benevolent, and above

all, more impartial, were careful not to pass premature judgment on a matter

of this nature: they knew that passion exaggerates both evil and good, and

that one should not rush to adopt the words of a

powerful and often unjust party.

We too will attend to this matter, but by prefacing it with all the

considerations necessary to draw the correct conclusions.

These facts, which seem to us hardly believable, are repeated every day with

impunity in our colonies. And how could it not be so, when the men charged

with maintaining the laws are those most interested in violating them!

Arbitrariness is therefore only the sad corollary of a state of affairs

whose origins date back to a time of conquest, plunder and brutal violence.

We know that this arbitrariness exists; philosophy has decried it; power

itself seems to reject a shameful solidarity, and yet nothing real has been

done to put an end to it. Everything has been deceit and lies, from the

illusory measures against the slave trade, to the laws which seem to grant

men of color the rights of citizens, and a justice which one could not

truthfully represent scales in the hand.

These causes, which, deriving from the overall regime of the colonies, would

seem foreign to the events of Grand'Anse, to which we will attend more

particularly, [11] are nevertheless attached to them by a

multitude of threads: for nothing in the fate of peoples, as in that of men,

is isolated, and the actual effects are often produced by causes lost to the

depths of time.

The colonies too, despite their distance from the motherland, felt the

effects of the great political commotion which regenerated

France. A long subjugation, largely exploited by

the aristocracy, had not been able to paralyze hearts so much that they did

not feel warmed by the rays of the sun of freedom. Men of color especially,

more advantaged than the unfortunate slaves, turned their eyes towards

France with love and confidence; they felt that each link which fell from

the chains of old Europe was for them a pledge of emancipation. The

emblazoned nobility, elevated to the rank of people, offered an edifying

lesson to the nobility of the skin,[12] which did not even

possess the prestige of the former's personal accomplishments. The

destruction of one was the sure guarantee of the destruction of the other.

Was not the emancipation of the people, who had long suffered the bondage

of the field, also a sign of freedom for the

slaves? There was therefore in the colonies what is still there today, an

absurd aristocracy clinging to its privileges and willing to go to any

length to preserve them, and on the other hand a population full of verve,

of energy, beginning to understand its rights and its dignity.

Such, then, was the position of the colonies when the July revolution,[13] so rich in prospects, made conceivable for a moment

the awakening of France. The new government, carried along, no doubt in

spite of itself, by the force of circumstance, not daring to lift the veil

which hid its ulterior motives, finally bowing before public opinion which

had just had its impact felt, erased the word regulations from

the article of the charter concerning the colonies. It declared that the

colonies would be governed by special laws[14]. This tacit recognition of abuses of all kinds, originating in the

corrupted system of ordinences, stoked the hopes of those who could still

put some faith in ministers' promises. It was because they did not believe

that a government born of democracy could so quickly forget its origin; they

did not comprehend that the preservation of titles of nobility, of a

so-called upper chamber, and above all of an exaggerated civil list were

milestones laid down by the nascent power to constitute itself on bases

similar to that which the popular arm had just crushed. Did not the

preservation of the titled nobility in the motherland,[15]

and the addition that was made to it of a Turcarets aristrocracy,[16] clearly impart to the colonies that, except for a few

slight adjustments, their aristocracy of skin would be preserved along with

most of its privileges.

Indeed these fine particular laws were rendered so illusory as

to match the ordinances' arbitrariness,[17] differing from

them only by the hypocrisy of the name. For example, is not the electoral

law, establishing the political rights of whites and of men of color, a work

of perfidious deception? On the isle of

Bourbonisle of

Bourbon and of CayenneCayenne,

where the whites are in overwhelming majority, the electoral qualification

and eligibility are fixed at a lower rate, for there is no fear of

competition; but in the colonies of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe

and MartiniqueMartinique, where the

population of color, quite numerous, is of average wealth, the tax is preemptively raised to an unattainable level.

Is there anything more perfidious, I would even say more odiously ironic,

than to thus concede the right while prohibiting the means. Would it not

have been truer to declare outright that only whites could vote?[18]

It became difficult, in the presence of this law of political organization,

creating or rather sanctioning a privilege, to allow for the action of the

popular will. The national guard, that admirable institution of the

métropole,[19] had a pale imitation in the colonies,

where both the name and the democratic element of election were carefully

banished.

If France has a national guard, the colonies have a militia whose officers,

appointed by the governor, are generally taken from the white population and

from among a few men of color. These, to keep a rank obtained by favor,

devote themselves unquestioningly to the governor and become his

accomplices. We hasten to say that, among those promoted, we count friends

who have not wavered in their political opinions, but not all of them are

so. When power makes itself odious by its partiality, it always corrupts the

men who make themselves its supporters. What bonds can indeed unite men who

find themselves in a position so false as the colonial militia and its

leaders? Trust? It does not exist. Fraternity? it would be vain to search

for it there. So there remains only force, and it is indeed felt

everyday.

In the judicial system, abuses abound, and they are always to the advantage

of the aristocratic class. The royal courts and the magistrates' courts are

constituted in such a way as to let the whites become judges and parties in

their own cause. Finally, despite the very text of the charter, provost

courts can still bloody the soil of the colonies by legally assassinating

the innocent people they want to get rid of.

Well! in the presence of this boundless arbitrariness, leaning on their

numerous privileges, the whites groan and complain that the government has

dared to touch the holy ark of their power, by diminishing some of their

privileges. Political rights, they possess them all; the judicial power is

in their hands; law enforcement, they direct and

command it; but it is not enough to suit their wounded pride. A principle,

admittedly without application, has been issued; the word equality was

spoken, was it not enough to offend those selfish and hard hearts for whom

every independent man who is not part of their league is but a worthless

rebellious slave?[20] Men of color, on the contrary,

confident in the government's feeble pledges of good will, waited patiently

for better days perfecting their political education so as to wield the

influence that they are entitled to in their country by their rights and

numbers. And what do they really want that is not wise and reasonable?

Placed in their land in the same position as the third estate in France

before the revolution, they then ask what this order commanded: liberty and

equality. But they are dealing with privileged people who are even more

tenacious than the nobility and clergy of France. These at least did not

have the impudence to deny the title of men to their adversaries.[21]

By what means, then, could the privileged recover the integrity of their

privileges? To ask the government for them was impossible, they would have

been told to bide their time; that the compromise was only a matter of

painful necessity; that, moreover, the liberties granted to the mulattoes

were purely illusory, being limited in reality to a few slight concessions

of sociability.[22] And furthermore these same concessions

often bend according to the whims of the aristocracy. These answers, which

would satisfy less impatient, and above all less prideful men, would have

deeply wounded those imperious masters whose despotism is exercised without

control over unfortunate slaves. It was therefore necessary to employ all

means, even calumny, to subjugate the class of color and crush it.[23] It had to be represented as factious, turbulent,

having sworn to destroy the whites and stopping at nothing, not murder, not

arson, to accomplish this. It is so easy to slander men who are not allowed

to defend themselves! To find guilty the enemy that one judges oneself! And

then the colonies also count among their ranks men who know how to create

conspiracies, foment them, cause them to arise at the right time, in order

to take advantage of them in their own interest. And what does it really

matter that the worthless blood of a few negroes comes to redden the ground!

What does it matter if a mulatto's head rolls on

the scaffold! Mere trifles, when you consider the glorious result expected

of it; that is, the bondage of the many for the benefit of the few. Besides,

the métropole offers a few examples which would seem to authorize the

colonies in this Machiavellianism.

And so we have seen the birth of these imaginary plots, these conflagrations

whose frequency during certain periods bespeaks frightful mysteries.

Innocents have been accused, thrown into dungeons, tortured, shot without

pity when they allowed themselves a few complaints. Neither sex nor age

could soften these ferocious men who subject their slaves to the most

sophisticated cruelties, and their gold, thrown at the heads of the

proconsuls of the great nation, hides large stains of blood from their

eyes.

Ah! if some day an eloquent pen tearing the funereal veil which covers our

colonies, would retrace the history of domination of the possessors of men;

if it evoked from the depths of their tombs the sad victims who are heaped

there every day, never would a country defiled by tyranny offer such

horrible pages.[24] All that we read of the Mésences, the

Caligulas, the Louis XIs,[25] all that our hearts refuse

to believe as too degrading for humanity, finds itself surpassed in the

nineteenth century by overseas Frenchmen. But these horrible scenes of

despotism have no place here, elsewhere we will reveal them by throwing the

names of their infamous authors among the ignominies of history.

THE GRAND'ANSE AFFAIR

While the public prosecutor’s office of MartiniqueMartinique laboriously gives birth to what it calls the insurrection of Grand'Anse, the

metropolitan government’s attention is drawn to those deplorable events by

the complaint of the principal victims addressed to the Council of State.

The plaintiffs are, among others, the heirs of the unfortunate

Lorville, who fell pierced by

seven bullets under a volley of musketry ordered to stop his escape; the

heirs of Fréjus, left for dead under the

blows of a Lasserre and since deceased as a result of

the violence exercised against him; the heirs of

Maurice

killed with his wife, and his daughter murdered

by a volley shot through their hut; Joseph AlbertJoseph Albert, deported in 1823, wounded in that

other shooting carried out on the prisoners of the Bonafon purgerie, through

the window gratings, etc., etc.

Admittedly, such victims, immolated not in a conflict, not in an armed

struggle between the authorities and such and such part of the population,

but murdered in their prison, in their home after having surrendered on the

faith of fallacious promises; such victims raising their voices to the

mother country seemed worthy of some attention on the part of the

ministry.

With what painful indignation will our fellow citizens of the colonies be

seized when they learn how the the Minister of the

Navythe Minister of the

Navy welcomed their request to the kingking in his council for

authorization to prosecute the authors or culprits of these saturnalia of

arbitrariness and bloodshed! The

ministerminister to whom the request

was communicated, according to custom, contented himself with the following

short and disdainful observations: “I will not discuss the facts because

the majority of the plaintiffs are included in the trial currently being

heard in MartiniqueMartinique. The MoniteurMoniteur of

March 17 has moreover published a report

emanating from the

governorthe

governor (that is to say, the

person whom the plaintiffs accuse) which, given the confidence he is

owed, cannot be entered alongside the account of individuals compromised

in the accusation.”

Then, soon shedding his affected respect for the position of the

accused,

the minister

the minister ends his letter by calling

them factious men, rehashing in banal and hackneyed phrases the

commonplaces of the day: “ That it would be dangerous to entertain their

recriminations at a time when so many and such culpable

attempts are directed against public peace. Such is the opinion of the

Department of the Navy on the recourse of plaintiffs to the Council of

State. We like to believe that this high jurisdiction will follow

inspirations that are more generous, more equitable, more friendly to

humanity.”

Yes, indeed, some of the plaintiffs–that is to say three, not

the majority–are destined to feature in the sad trial which is

currently being staged in MartiniqueMartinique; but the others,

but those who died unarmed, prisoners, under the soldiers’ bullets, those

will not go to the assizes. How can one counter in cold blood the complaints of their wives and children with this cruel

denial of justice? Whatever the result of the trial, even if it were to

prove the existence of the alleged conspiracy, could it ever justify the

local government’s massacre of conspirators who had been captured, disarmed

and who were held prisoners, kept in sight, besieged on all sides by law

enforcement? will it absolve local authorities for letting these unfortunate

victims fall under a rain of murderous lead?

We know today in France what procedure was initiated because of the events of

Grand'Anse. We have before us a printed copy of the order for remand to the

assizes, issued by the indictment chamber, against 117 defendants. This

document notes what we have just said, that only three of those who have

addressed a request to the Council of State are referred to the Assizes of

Saint-PierreSaint-Pierre. This decision also authentically

establishes the facts stated in the request, and which the Minister of the NavyMinister of the Navy disdains

to discuss, in particular the shooting carried out on

Lorville and two other prisoners fleeing with

him, by express order of the captain in command (pages 51 and 55

of the indictment). As for the massacre of the

Maurice family, it is

acknowledged, albeit in a somewhat distorted account, by this same

MoniteurMoniteur of March 17, whose sincerity seems

less doubtful than that of the plaintiffs, but from which nevertheless the

Minister has removed certain, overly clumsy, passages of the governorgovernor's report. Are facts

so incontestable unworthy of the solicitude of the government? do they not

deserve examination, investigation, adversarial discussion with the

MinisterMinister? There are

a host of others also specified in the request, all those who denounce to

the métropole for the hundredth time the systematic oppression of the

classes of color, the daily provocations directed against them, the

continued denial of all their rights in defiance of the laws that grant

them, finally all those others which give true color to the events of

la Grand'Anse. But what does it matter! all these

facts of high political and social importance will be omitted, concealed,

denied if necessary, and in all cases excused. What the so-called official

and authentic relations of the MoniteurMoniteur will

show to the colonies, to France, is one hundred and seventeen conspiratorrs appearing in court

under the weight of a 300-page charge, all accused of conspiracy, for the

government of MartiniqueMartinique needs one; then each one in

particular accused of having looted two jars of tafia and two jars of rum

from Seguinot; or from

Desmadrelles, soap, candles, a

horse's currycomb; or from Lereynerie, a

bottle of jenever (pages 85 and 86 of the order for reference). And all this

printed by the government of the colony over 200 pages, pompously titled, by

the most ignorant of magistrates, Insurrection of

Grand'Anse.

What of the permanent conspiracy against the rights and personal safety of

the population of color! the permanent insurrection of the whites against

the laws of the métropole, every day shamelessly spurned by these colonists

from the north of the colony, made infamous by the mass proscription of

1823, by their declaration to the government that they would never recognize

men of color as their equals! What is being done about these conspiracies

that reappear every day, always going unpunished?

Wretched colonies! will it ever be your fate to pointlessly show your wounds

to the motherland, only for our incredulous rulers to not even deign probe

it with their fingers!

A WORD ON THE SPEECH DELIVERED BY MR. ISAMBERT AT THE SESSION OF THIS PAST

MAY 8TH.

If experience is the touchstone of all legislation, we cannot disagree that

the organic law for the colonies promulgated in 1833 is essentially

defective; for the results it has produced are detestable; Mr. IsambertMr. Isambert demonstrated this abundantly. The

commission charged with examining this law unanimously recognized, he tells

us, that it was desirable that men of color be admitted to the colonial

council. Well! With the exception of French

GuianaFrench

Guiana, in each of our colonies and notably in the most

important of all, MartiniqueMartinique, this council

was formed exclusively of white colonists. This fundamental flaw in

composition is an insurmountable obstacle

to the introduction of the reforms that the situation in our colonies

urgently demands. In support of this assertion, Mr. Isambert cites a fact

that is well worth repeating here: the governor of Martinique presented

various draft royal ordinances to the colonial council regarding the

reorganization of militias, the form and conditions of manumission, the

advice to be given regarding municipal and judicial organization, etc. Here

is how the council responded: “The colonial council pays tribute to the

government's intentions on behalf of the king, but often the measures

taken to achieve this goal, instead of attaining it, lead to disastrous

results. We will immediately focus on the 1834 budget.” Frankly, is

this not a clear rejection of the governor's proposals? Is this not telling

him that his suggestions are not even worth considering? Therefore, without

a second thought, the council will immediately move on to the budget. Does

this display of disdain and directness not perfectly illustrate the

aristocratic arrogance of our very high and mighty masters by right of

whiteness?

Vis-à-vis this impertinent response, the honorable deputy placed the generous

words by which the colonial council of French Guiana not only promised its

assistance in all the improvement projects presented by the governor, but

even committed to initiating reforms on many points. Why were these

proposals received so differently in one of the colonies compared to the

other? It is because the 1833 law was even more restrictive in granting

suffrage rights to people of color in Martinique and GuadeloupeGuadeloupe, than to those residing in French Guiana.

“It wouldn't be the case,” says Mr. Isambert, “if a few men of

color (I say some because I don't claim to want the classes,

which have remained in complete isolation up to now, to have the same

advantage as the Creole class), but again, if a few men of color were

admitted to the colonial council.” One can see that the illustrious

legal expert is here displaying a conciliatory attitude and playing a bit

too nicely to the colonial aristocracy; therefore, it is our duty to protest

against a

concession that would do nothing less than uphold privilege and be an attack

on the great principle of equality.

We would regret it if one were to perceive even the shadow of a reproach in

our words. We know all too well Mr. Isambert’s conscientious integrity and

love of justice to find in this departure from a principle anything other

than a momentary lapse. Moreover, Mr. Isambert's generous instincts quickly

lead him back to common law. A few lines further, he indeed speaks out

against the bias of the electoral system, which, out of ten voters, only

admits one voter of color, even though the population of this class is three

times that of the whites. This obviously denies every man of color access to

the colonial council. On this matter, it is essential to return to the

principle proclaimed by the Constituent Assembly, which granted the right to

vote to every free man, aged twenty-five or older, owning property, or

residing in the municipality for two years and paying a tax.

A portion of the discourse we are examining is dedicated to highlighting the

monstrous flaws that abound in the judicial organization of Martinique,

particularly in criminal justice. There, it seems that everything has been

designed to deprive unfortunate litigants of any chance of acquittal. For

instance, a court of assizes is composed of three counselors from the royal

court and four members of the board of assessors, an institution that

reflects the jury. All of them are exclusively selected from the white

class. The four assessors are drawn by lot from a list of thirty members,

but this list is further reduced by illnesses, absences, or any other

impediments to twenty men per assize; the decision is made by the majority

of votes from this kind of jury combined with that of the court, consisting

of three judges. So, assuming unanimity from the court and the jury, the

verdict is rendered with a number of votes lower than what is required of a

jury in France; thus, four votes are sufficient in the colonies to pass a

death sentence, whereas in France, eight are required for a criminal

conviction, and English law, even more humane, demands unanimous jury

agreement for all types of convictions.

If you add to all of this the fact that in the colonies, men of

color are constantly in competition with whites, and the intense and bitter

animosities that divide them often lead to disputes that are interpreted as

conspiracies, wouldn't you conclude that placing the sword of justice solely

in the hands of the Creole inevitably turns it into an instrument of revenge

and cruelty? That it leaves men of color at the mercy of their enemies, and

to maintain such a state of affairs any longer would demonstrate a barbaric

indifference to human life and a heinous disregard for the sacred laws of

justice. Judicial reorganization is all the more urgent because, as a result

of the sad events in Grand'Anse, a hundred and seventeen people are

currently facing a capital charge.

THE NEED FOR EDUCATION IN THE COLONIES

Men of color have owed improvements in their condition to the progress of public

opinion. Since 1830, they have finally obtained the political rights that were

denied to them for so long by individuals who were still interested in

maintaining their subjugation. The humiliating distinctions that justly offended

their wounded self-esteem and deprived them of the exercise of a natural right

have finally disappeared. Today, they are an integral part of the great French

family without restrictions. They are French citizens or eligible to become

such. They can rightfully take pride in this qualification, which allows them to

sit in the midst of the sovereign people, sharing in its sovereignty. However,

they should also know that this civilization's blessing has imposed new

responsibilities on them, the fulfillment of which is essential to maintaining

the high status they have achieved through the triumph of freedom.

It is to science that civilization owes its triumphant progress through the

prejudices accumulated over the centuries. More precisely, civilization itself

has been nothing more than the conquest of science. This is the noblest

achievement of the human mind, and freedom, the offspring of civilization, could

have no other origin than its mother. Science, civilization, and freedom are

therefore inseparable correlates that presuppose and call each other, and they

cannot exist separately.

One would have to hold a deeply false idea of freedom to believe that it could

securely establish itself in a country inhabited by men hostile to or, at the

very least, apathetic towards education. The air one breathes in the abode of

ignorance, prejudices, and shameful passions is mephitic to freedom. Freedom

wants to be worshiped only by men with generous ideas and elevated sentiments

who, through study, may appreciate her benefactions, offer her a pure and worthy

devotion, and defend her against the attacks of her enemies.

Men of color must, therefore, abandon the independence they are so proud of today

and the hope of acquiring any influence in the affairs of their country if they

do not promote education among themselves. If a base and disastrous selfishness

prevents them from making the necessary sacrifices for the education of their

children in France. Today more than ever, they must feel this need: did not the

colonial council of MartiniqueMartinique Martinique, in

its first session, recently abolish the monitorial schools created by Mr. d'ArgoutMr. d'Argout during his time as Minister of the Navy?

In the current state of affairs in the colonies, the political emancipation of

men of color and their inclusion in the great French family is undoubtedly a

cause for joy for each of them. However, what a source of humiliation do the

majority of them find when, in the exercise of their new rights, they are put in

contact with individuals well-versed in business and possessing specialized and

diverse knowledge.

The education of women is even more backward than that of men. A regrettable

silence, when they are in society, diminishes their charm and takes away what

would be most appealing.

Don't place them alongside one of those Parisian women whose conversation is so

lively, pleasant, and captivating. Nevertheless, nature has not been any less

generous to the children of the colonies than to those of France: provide young

individuals from the colonies with the same education, and soon the riches of

their passionate imagination will be revealed. They will shine and captivate,

just like our witty French women, with the diversity of their conversation and

the indescribable charm of their remarks.

We implore men of color not to judge our criticisms as

overly severe. It is a friendly voice that speaks to them. Let them heed the

advice of men who constantly fight for the triumph of their cause and fear the

possibility of their emancipation being incomplete or even fruitless. If men of

color do not know how to break free from the state of torpor in which they

languish, let them tremble in their apathetic ignorance. The links of their

chains are scattered and broken, it is true, but an ambitious and bold hand

could weld them together once more. A governor of the caliber of a FreycinetFreycinet and a DonzelotDonzelot, can make them lose all their advantages. A prosecutor

general as capable as RICHARD LUCYRICHARD LUCY, can annul

even the most firmly established concessions. Let them consider the events; they

are far from offering them complete security.

Their freedom will only be stable, unassailable, and their status as French

citizens definitively secured when their children attend our schools and join

various branches of the administration in large numbers. We will have confidence

in their future only when we see them enrolling significant numbers of students

in institutions of higher learning such as PolytechniquePolytechnique, Saint-CyrSaint-Cyr,

Medicine, Law, Commerce, and the Navy. It is then, and only then, that they will

acquire the local influence and respect they covet and achieve the integration

from which they are yet so far removed.

As this is a matter of vital importance about which we could not possibly call

the attention of our friends from the colonies too much, we will dedicate a

series of articles on this same subject, and will propose a plan to realize our

educational project and to neutralize in the same movement the efforts of the

colonial aristocracy, which toward depriving the masses of education in order to

better exploit them.

THE ELECTORAL QUESTION.

A new question has arisen in electoral matters in the colonies: whether an

unmarried woman can delegate her contributions to her legally recognized natural

son.

The Director General of the Interior in MartiniqueMartinique, acting as prefect, has

refused to recognize such delegation for the following reason: “To grant an

unmarried woman the right to delegate would be to give an arbitrary

extension to a provision that is already inherently exceptional by its

nature.

We have decided and hereby declare the following: Mr. Sugnin (Philippe-Simon-Eudoxie)Mr. Sugnin (Philippe-Simon-Eudoxie) in the current state

of affairs, cannot be registered on the electoral list of the 4th

constituency. At Fort-RoyalFort-Royal

(MartiniqueMartinique), April 19th, 1833

Signed

viscount ROSILYviscount ROSILY.”

The citizen affected by this decision neglected to appeal to the royal court for

its revision within ten days of its notification, as stipulated by the law.

Since this issue may arise frequently in the colonies, where a considerable

number of unmarried women with legally recognized natural children can be found,

we will provide observations against this decision in line with the spirit of

the law.

The argument upon which the decision we are contesting is based is the same one

that was opposed to us during the Restoration when we argued, according to the

law of February 5, 1817, that the delegation right belonged to divorced women

and women legally separated, in favor of grandsons-in-law as well as

sons-in-law.

How did the Council of StateCouncil of State respond, given that it

was dominated by the system of government of the time, which aimed to restrict

rather than extend the exercise of political rights?

Following a request presented by us on behalf of Mr.

ArouxMr.

Aroux, now a deputy (February 11, 1824), it responded that “to

grant the grandson-in-law a right that the law had limited to the son-in-law

would be to give an arbitrary extension to an exceptional provision.” The

1831 law has put an end to this quibbling.

The 1817 law did not mention the adoptive mother; however, in a decision passed

on September 9, 1830, the Royal Court of NancyRoyal Court of Nancy

ruled that she had the right to delegate. Since then, even though divorce has

not been reinstated, upon our proposal in 1831, the Chamber

of DeputiesChamber

of Deputies has had no qualms admitting divorced women, like

legally separated women, to the delegation right.

Isn't the unmarried woman, who cannot exercise political rights attached to

property ownership by herself, in exactly the same social position as the

divorced woman and the legally separated woman?

In France, In France, where morals are much stricter than

in the colonies, one could consider Mr. Viscount de

RosilyMr. Viscount de

Rosily 's decision as a tribute to good morals.

But he did not want to include this reason in his decree; it would have been a

condemnation of an ingrained practice in the colonies, which magistrates like

Mr. DessallesMr. Dessalles, in the annals of

MartiniqueMartinique, have argued is justified by the heat of

the climate.

We believe that, in addition to this consideration, there is another more

compelling one. The number of voters is greatly restricted in the colonies,

especially in the colored class. Far from there being a political motive to

restrict the exercise of rights created by the 1833 law in favor of citizens of

this class who could provide the desired property guarantees, the most vigorous

support has been expressed for their expansion by the king's commissioners and

the defenders of the law within the commission of which we were a part, but also

within the chamber and beyond.

The decision in question is therefore contrary to the spirit of the law, the

spirit of all electoral legislation, which, when in doubt, seeks not to restrict

the right but to expand it. ParisParis, July 2nd,

1834. ISAMBERTISAMBERT.

Favores ampliandae. Nothing is more favorable

than electoral law. The principle of delegation is the kind of equivalence

that nature and the law establish between the mother and her children,

una et eadem persona. If the law

specifically mentions the widow and the legally separated woman, which

implies marriage, it is because it refers to the most common case, but the

law is indicative in this regard and not restrictive. ODILON-BARROT.ODILON-BARROT.

A DE FACTO FREEDMAN’S APPEAL.

A significant question regarding slavery has come before the Court of CassationCourt of Cassation.

Two young men were convicted by the Assize Court of French

GuianaFrench

Guiana, along with a free man of color who did not file an

appeal in cassation. Both of his co-accused were considered slaves throughout

the proceedings. However, one of them, Cyprien

JacquardCyprien

Jacquard, argued that he was in a state of manumission because he

had been bequeathed by his master to his emancipated mother, so as to provide

him and other children with a means of livelihood.

When this case was first presented, the Court of CassationCourt of Cassation was

struck by the odiousness of considering a child as a slave to his mother, whom

she could potentially sell. It could happen that a mother was bequeathed by a

master to her own son, and he might also be in a position to alienate her. Would

such a reversal of the laws of nature be sanctioned by colonial legislation?

The court, in a ruling dated January 10, 1834, ordered that the facts be verified

before making a decision on the appeal.

As a result of the information gathered in compliance with this ruling, it was

found that Jacquard's mother, upon gaining her freedom from her master, had

received her children born of him, as well as her own mother, as part of her

bequest. Subsequent to Jacquard's conviction, this woman made the required

declarations at the civil registry office, as per the Ordinance of July 12,

1832, to obtain her son’s emancipation certificate.

Given this situation, the Attorney General of the colony argued that Jacquard,

the appellant in cassation, was not admissible to file an appeal in cassation.

This was because, as per the colonial ordinance of July 20, 1828, Article 9,

which the Criminal Procedure Code, since promulgated, does not override, slaves

are prohibited from using this appeal, and Jacquard was still a slave at the

time of the alleged crime and his conviction.

At the hearing on June 26, Counselor DehaussyCounselor Dehaussy

reported on this matter and, without examining the grounds for the appeal,denied it in consideration of the state of slavery in

which the appellants found themselves.

This magistrate did not hide how distressing this situation was and how desirable

it was for slavery to be declared incompatible with such intimate family

relationships. He announced that, through his dispatch, the Attorney General

assured that a bill regarding this incompatibility would be proposed in the

session of the colonial council. However, he had not found a legal basis under

which the Court of Cassation could release young Jacquard from the state of

slavery in which he found himself.

Mr. ParantMr. Parant, the Attorney General, concluded in

this direction, invoking the admission Jacquard had made during his

interrogation and the steps taken by his own mother to secure his

emancipation.

The admission recorded in his interrogation amounted to this:

“My name is Cyprien, also known as Jacquard; I am sixteen years old, and belong

to the colored caste; I am a carpenter by profession; I belong to my mother,

with whom I live in CayenneCayenne, where I was

born.”

The court, in a ruling dated June 26, started from this point of fact and

declared that there was no need to examine the merits of the appeal.

During its discussion of the case of the de facto freedman LouisyLouisy, this court had seemed to us to better

understand its high mission.

It had judged that freedom is a right and that slavery should be confined within

the strict limits granted it by the law, and that one should not treat as a

slave someone who has de facto ceased to be one. Consequently, despite the

colonial ordinances that obliged de facto freedmen in risk of being declared and

sold as slaves for the benefit of the colonial domain, to produce their freedom

papers, the court, focusing only on the law and the fact of freedom, declared

Louisy’s appeal admissible.

Was this not the occasion to render a similar ruling? Neither in Roman

legislation nor in the Code

NoirCode

Noir (the edict of 1689) do we find consecrated such

immorality, by which a father ormother can become,

arbitrarily, the property of their child. For, with such a doctrine, one would

be obliged to tolerate that they sell the authors of their days in the market

and receive the price. The Romans also abolished the ancient law that gave the

father the right of life and death over all members of his family.

The Code Noir allows for several cases where freedom results as of right from a

status incompatible with slavery. This includes the case where a master has

appointed a slave as his executor or as a guardian for his children.

How can one reconcile the status of being a son with that of being a slave to his

mother? A son, according to natural law and the civil code published in the

colonies, is bound by duties entirely different from those of a slave towards

his mother.

The mother also has particular duties towards her child. If this child becomes

unable to provide for their subsistence, is she not obligated to nourish them?

And how could such a law not be above the unjust law of slavery?

It is regrettable that the Court of Cassation left this important question

without resolution and only focused on the apparent fact. By judging in this

manner, did it not violate Article 7 of the 1832 ordinance, which ensures that

those who are de facto free have the benefit of an appeal in cassation?

In declaring that he belonged to his mother, did not young Cyprien Jacquard

prove, by that fact alone, that he had no master, and that there existed between

him and his mother nothing but the natural and civic bond?

TRAITS OF CRUELTY.

It would be a lengthy story to recount the deeds of revolting cruelty that some

slave owners in our colonies inflict upon the unfortunate slaves. Every day,

torn by the whip of the overseer, deprived of their coarse sustenance, they

slowly perish in incessant torment; only greed and never humanity sometimes hold

back these cruel masters who fear losing a venal

price with the death of a slave. But when the slave, crippled or old, can no

longer provide the same services, when his presumed profit on the plantation no

longer exceeds the expenses he incurs, oh, then! No consideration can hold them

back anymore, and just as one breaks an old, disabled piece of furniture, so do

they mercilessly cause to perish the man they tore from his family when he was

young.

Sometimes, a whim, a resurgence of barbarity seizes a master, and no matter what

potential prejudice such atrocious satisfaction might possibly bring him, he has

a man, his peer, his equal, sacrificed. These acts of cold cruelty are so far

from our mores that we, born in the colonies, cannot comprehend them. Often, an

honorable skepticism guards us against the accounts of our correspondents. Would

to God that they were all false! We would be the first to proclaim them so, and

our hearts would not be burdened by painful impressions.

Here are two new facts to record in the long list of crimes that makes up

colonial history. There we not only see a colonist committing a heinous murder,

but another ordering it to be carried out by his slaves, thus demoralizing these

unfortunate individuals who, at the risk of their lives, could not refuse the

orders they received.

In MartiniqueMartinique, un landowner in the

commune of La Rivière Pilote, apparently convinced

that he had reason to complain about his slave Gabriel, summoned six slaves from

his workshop on April 16 and ordered them to bring him Gabriel's head. The

slaves promised obedience.

Gabriel, unofficially informed of his master's intentions, went to see him and

offered 3,535 francs for his redemption. The master replied that he would

consider it. Although this reply was nothing short of satisfactory, the

unfortunate Gabriel set about realizing his funds, and went to the market town

of Le Marin to sell his flour. As he was leaving, six negroes ambushed him,

drove him to the sugar mill, tied him to a calabash tree and killed him. One of

the executioners then went to the owner, who, having heard the story of the

murder, simply replied coldly: “That is well” .

However, the planter, having gone to the place where Gabriel's mutilated corpse

lay, couldn't stand the dreadful sight for long: he withdrew, and with the help

of his sugar maker, spread the rumor that Gabriel had been killed by a mule. He

sent word to the Commune's Commissar, but public rumor had beaten him to it, and

the Commissar came with the Justice of the Peace and two doctors to perform an

autopsy on the corpse. The type of death was then recognized, and among other

wounds, a gunshot wound to the lower jaw. A report was drawn up and deposited at

Fort-RoyalFort-Royal.

In the same colony, in the commune of Macouba, a wealthy

owner was accused by the public of killing his slaves. The public prosecutor

went to the property and found an unfortunate woman lying lifeless. The master

had cruelly castigated her, and she had expired under the lashes. To ascertain

whether the corpse was still alive, the cruel master went so far as to pierce

his victim's belly with a hot iron. The courts are investigating the case, but

the colonist accused of the crime is on the run. The new governor, Mr. HalganMr. Halgan, has hastened to send details of this act of

colonial monstrosity to the Ministry of the Navy.

It is to be hoped that, in the interests of justice and humanity, such crimes

will not go unpunished. The honor of the government and the salvation of the

colony are at stake; for where the reign of justice ceases, the right of might

and violence is born.

FRANCE.

PARIS.

CONVOCATION OF THE CHAMBERS.

The following ordinance is published in the MoniteurMoniteur of July 1, dated

June 30 and countersigned by Mr.

ThiersMr.

Thiers :

“Art. 1. The provision of our ordinance of May 25 of this year, which convened

the Chamber of Peers and the Chamber of Deputies for August 20, 1834, is

revoked.Art. 2. The Chamber of Peers and the

Chamber of Deputies are convened for the next July 31.”

The MoniteurMoniteur publishes immediately after, but in the

non-official section, the following communication which explains the

significance of this measure:

“The meeting of the chambers was scheduled for August 20th next. It is now

brought forward and set, by this day's ordinance, to July 31st. The king,

who in August will be traveling to the southern provinces he has not yet

visited, did not want to be absent at the time of the chambers' assembly.

Furthermore, this assembly does not have its usual importance: it is

convened for the execution of Article 42 of the Charter. However, the

government cannot and should not commence their work at that time; no bills,

no budget proposals could be ready. Besides, our parliamentary traditions

fix the period for the chambers' work between the months of December and

May, during the winter season. To begin them in the middle of summer would

be an unfortunate departure from established customs. Three hundred deputies

from the former chamber, now part of the new one, have already spent five

months in Paris this year and could hardly return in July. It is, therefore,

appropriate to postpone the work to the customary time. Consequently, after

convening the chambers on July 31 and having them in session, the king,

using the right of prorogation, will prorogue them until the end of the year

to begin the important work of the new legislature at that time.”

Proroguing the chambers before they are constituted would be another outrage to

add to all those we witness daily. The chambers cannot be prorogued before the

new powers of the deputies are verified. If this violation of the Charter were

to occur, we will return to this subject.

ELECTORAL NEWS.

We believe it is necessary to inform about the election to the new legislature of

deputies who have always taken a particular interest in colonial issues.

Mr. DELABORDEMr. DELABORDE was elected both in

ParisParis and Étampes (Seine-etOise). Undoubtedly, one might wish for a bit

more severity from this honorable deputy toward the advisors to the crown.

Nevertheless, we will never hesitate to acknowledge Mr. Delaborde's pure

intentions, and we are confident that the cause of people of color will always

find support and protection in him.

Mr. DE TRACYMr. DE TRACY was elected in two electoral

districts in Allier. This choice honors the constituents even more than the

representative. Mr. de Tracy is the advocate of all noble causes and, in that

capacity, the most genuine and eloquent voice for the oppressed in our

colonies.

Mr. ISAMBERTMr. ISAMBERT was reelected in Vendée

Luçon. We congratulate the voters of Luçon for renewing the

mandate of the courageous defender of the deportees from MartiniqueMartinique, a man as upright as he is enlightened, who never

lets an injustice pass without denouncing it and who has never failed the sacred

cause of humanity.

Mr. GAETAN DE LA ROCHEFOUCAULDMr. GAETAN DE LA ROCHEFOUCAULD was elected in the

department of Cher. We can only applaud this choice, which sends one of the most

zealous champions of the abolition of slavery back to the chamber.

Among the most regrettable losses for people of color in the recent elections, we

must first mention Mr. Eusèbe SalverteMr. Eusèbe Salverte.

In the 5th electoral district of Paris, Mr. Thiers Mr. Thiers defeated this honorable citizen. It is the

victory of intrigue over patriotic austerity personified in the person of Mr.

Salverte. Mr. the Minister of the Interior is the pale reflection of Mr. de TalleyrandMr. de Talleyrand, that archetype and patriarch of

political roués, just as Mr. Salverte offers us the pure and living image of the

virtuous CarnotCarnot.

Messrs. CharamauleCharamaule and MérilhouMérilhou were also not re-elected. Let us hope that the

re-elections that will take place due to double nominations will rectify this

loss or, rather, this injustice.

MISCELLANEOUS NEWS.

“The following article, published by the MoniteurMoniteur of July 2, is

undoubtedly an indirect response to the new information provided about the

state of the colony of MartiniqueMartinique.

In a letter dated May 21st, Vice-Admiral Halgan, Governor

of MartiniqueVice-Admiral Halgan, Governor

of Martinique, reported to the Minister of the Navy on a tour

he had just made to several communes of the colony.

The following passages are noteworthy in this report:

“I am happy to report that the population is perfectly calm in all the

areas I visited, and everyone is focused on taking advantage of a

favorable year for the harvest.

I conducted a thorough examination of the internal management of the

plantations and the treatment the slaves receive from their masters. The

administration generally seemed to me paternal and wise. Punishments are

falling into disuse, and on most of the properties where I stopped, I

observed that the masters had affection for their slaves who, without

concern for the future, are content with the present, attached to their

homes, the small comfort they enjoy, and willingly engage in work that

does not exceed their physical capabilities.”

Thus, Vice-Admiral Halgan's testimony regarding the situation of the slaves

in Martinique is very similar to that of Rear-Admiral

DupotetRear-Admiral

Dupotet, whom he replaced, and who himself had merely

confirmed the reports of his predecessor on this matter. This unanimity of

opinions from individuals holding high positions and who were well-placed to

know the truth seems to us of a nature to dispel many unjust prejudices and

convince that the lot of the slaves in French colonies today leaves little

to be desired for friends of humanity.

Would it not be permissible to point out that this unanimity among the

governors might only prove one thing, namely, that they have been, since

their arrival,influenced by the same factors? And

as for Mr. Halgan in particular, who has barely arrived on the island, who

has seen but a few plantations, and who dismisses the pleas presented to

him, he is an authority that can, at this point, be challenged.”

(Messager.)

If one is to believe the official newspaper, wouldn't the slaves be in a real

el dorado, enjoying the tranquil and pure happiness that is

only found in the shepherds' tales of Durfé and Florian? One must truly lack

shame to advance such obviously false claims. Let the

MoniteurMoniteur then provide us with

Admiral Halgan, report without reservations, and let it

tell us whether the masters mentioned by the admiral as having murdered slaves

are cherished by those who have witnessed the mutilation of their brothers. We

call for the complete and unaltered report, but they dare not

present it in its entirety, for it would suffice to reveal the extent of the

slaves' happiness. In an upcoming issue, we will examine this report and address

the MoniteurMoniteur's deliberate omissions.

FRENCH COLONIES.

CAYENNE.CAYENNE.

We receive the following letter from CayenneCayenne,

containing considerations on the electoral law, the importance of which our

readers will understand.

“The colonial legislation published in GuianaGuiana,” it says, “is the subject of numerous complaints.

Men of color have found truel disappointment in the electoral law; hence,

those who could meet the 200 francs census have shown great indifference in

participating in the elections. In contrast, whites have viewed the

consecration of their privileges with a deep sense of satisfaction. Since

the bill for the abolition of slavery has passed in England, our aristocrats

would be willing to introduce two men of color into the colonial council out

of sixteen, provided they are obedient individuals with no connection to

BissetteBissette, that eternal enemy of colonial

interests.”

SUPPLEMENT

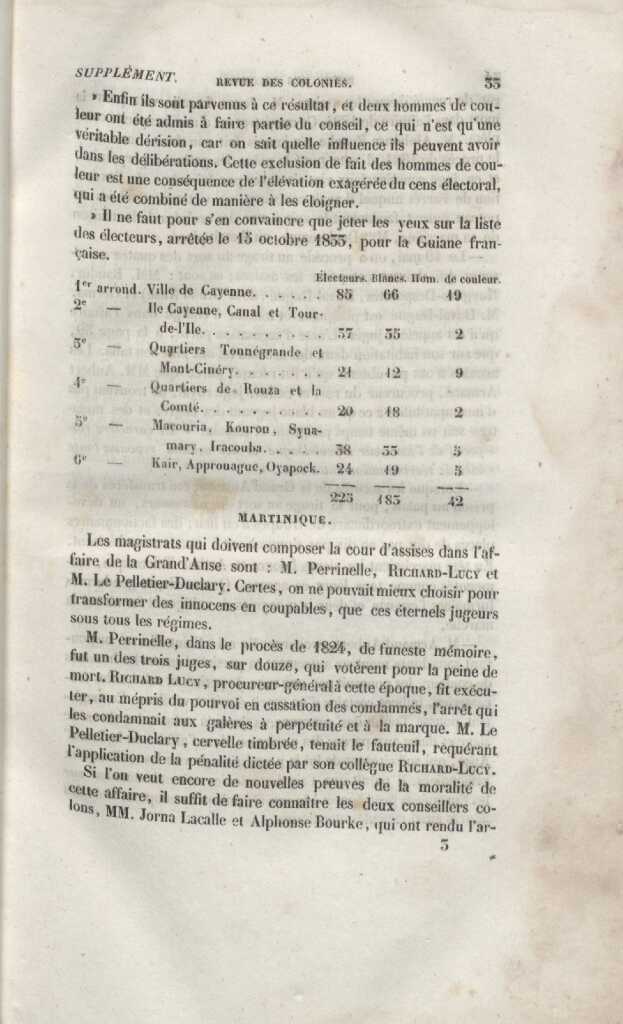

“Finally, they have reached this result, and two men of color have been

admitted in the council, which is nothing but a true mockery, as one knows

what influence they can have in deliberations. This de facto exclusion of

men of color is a consequence of the exaggerated elevation of the electoral

census, which has been designed in such a way as to keep them away.

To be convinced of this, one need only look at the list of voters,

established on October 13, 1833, for French

GuianaFrench

Guiana.”

Electors

Whites

Men of color

1st district City de Cayenne

85

66

19

2nd - Cayenne Island, Canal and Tour de-l'lle.

57

55

2

3rd - Districts Tonnégrande and Mont-Sinéry.

21

12

9

4th - Districts de Rouza and la Comté.

20

18

2

5th - Macouria, Kouron Synamary, Iracoula.

38

33

5

6th - Kair, Approuague, Oyapock.

24

19

5

MARTINIQUE.MARTINIQUE.

The magistrates who are to compose the assize court in the Grand'Anse case are:

Mr. PerrinelleMr. Perrinelle, RICHARD-LUCYRICHARD-LUCY and Mr. Le

Pelletier-DuclaryMr. Le

Pelletier-Duclary. Certainly, to transform innocent individuals

into guilty ones, one could not have chosen better than these eternal judges

under all regimes.

Mr. Perrinelle, in the infamous 1824 trial, was one of the three judges out of

twelve who voted for the death penalty. RICHARD LUCY, the prosecutor-general at

that time, carried out the judgment that sentenced them to perpetual hard labor

and branding, in disregard of the appeal to cassation by the condemned. Mr. Le

Pelletier-Duclary, a troubled mind, presided, requesting the application of the

penalty dictated by his colleague RICHARD-LUCY.

If one still needs further proof of the morality of this case, suffice it to name

the two colonial counselors, Messrs. MM. Jorna

LacalleMM. Jorna

Lacalle and Alphonse BourkeAlphonse Bourke,

who rendered the orderfor the trial before the

assizes. Mr. Jorna Lacalle voted for the death penalty in the 1824 case. This

magistrate is utterly incompetent. Mr. Alphonse Bourke never completed his law

degree, but in the 1824 trial, he voted for the penalty of perpetual hard labor,

and as a conscientious judge, he personally ensured the execution of the

judgment to which he had contributed. His victims, bound to the stake, could

easily see him from one of the windows of the house of his godmother, Mme

Duclésemur, where he was stationed.

-On May 19th, the drawing of lots was carried out for the four assessors who will

sit on the assize court. They are: Messrs. BaudinBaudin, Huygues-DespointesHuygues-Despointes,

Duval-DuguéDuval-Dugué (of Grand'Anse) and GermaGerma. Mr. Duval-Dagué is a complainant and a key

witness in the case he is called to judge. The indictment states, on page 39,

that two of the accused looted rum on his plantation. The accused were unable to

have him recused because Messrs. Aubert-ArmardAubert-ArmandAubert-ArmardAubert-Armand, the

public prosecutor, and Selles, the royal judge, did not

find any incompatibility in a white man judging blacks and mulattos while being

a complainant and a witness.The respective character of Assessor

Duval-Dugué and the accused precludes any idea of recrimination between

them...

-When the accused from Grand'Anse were transferred from the prison to the

courthouse for the drawing of lots for the assessors, an extraordinary

deployment of troops took place; sentinels placed every ten paces prevented any

gathering. Leading were Messrs. LéonceLéonce and

Arthur TélémaqueArthur Télémaque, handcuffed like all

their co-accused. An escort of eighty gendarmes was formed, and two companies of

riflemen brought up the rear.

-Mr. Armand AubertM.

Aubert-Armand, the public prosecutor in Saint-Pierre, no doubt

wanting to show his bias towards men of color, pursues them with a series of

petty and miserable harassments, certain signs of a narrow and petty mind. This

magistrate pushes the limits of propriety to the point of refusing the titles of

Mr. and Mrs. to the relatives of the defendants in

the Grand'Anse case who requested from him permission to see the unfortunate

prisoners. It seems that the colonial atmosphere has a powerful effect on

Europeans predisposed to vanity, as they quickly adopt such ridiculous and silly

attitudes.

Shortly after the July Revolution, this same magistrate, appointed royal judge in

CayenneCayenne, did not hesitate to seek advice

from one of the representatives of people of color in ParisParis. He wanted, he said, to enlighten himself in order to

enforce the laws despite the ill will of the colonists. At that time, it is

true, he often met this representative in the salons of the Minister of Justice,

where he was received. This explains many things.

GUADELOUPE.GUADELOUPE.

The political situation remains the same; however, there is more tranquility,

which probably results less from the satisfaction of the parties than from the

weariness they feel from these continuous and fruitless clashes. There has been,

therefore, a sort of truce during which young white and colored people have come

closer, shaken hands, and mutually promised to live as brothers from now on. May

this commitment endure!

The colonial council has not formulated a single decree; it has, until now, only

engaged in opposition to the proposed improvements. Thus, the government,

foreseeing that it will be overwhelmed sooner or later by this new institution,

is not very pleased with it.

The consolidation of the National Guard remains a question; the council has not

yet made any decisions on this matter.

BOURBON.BOURBON.

The situation in this colony is beginning to feel the effects of some

improvements made to the colonial system since the July Revolution. Caste

prejudices are decreasing and will eventually disappear as institutions receive

further development.

There is hope that in the upcoming elections, people of color will be appointed

to the general council. Already, a large number of votes are assured in favor of

Mr. Louis ElieMr. Louis Elie, who enjoys great respect in

the country.

There is some activity in the organization of militias, and, in general, there is

no reason to complain about local authorities. As for trade, it is virtually

non-existent, and prospects for the future are quite bleak. The re-election of Mr.

Sully-BrunetMr.

Sully-Brunet, as a delegate, which seemed doubtful, now appears

to be assured.

ALGER.ALGER.

This important possession, whose colonization we hope not to be delayed much

longer, is beginning to enjoy some advantages - the inevitable results of its

geographical position and the fertile land that extends from the sea to the

foothills of the Atlas Mountains. The cessation of hostilities by the indigenous

people, renewed confidence, and more active commercial transactions are the

first outcomes of a fairer administration; indeed, justice is the primary good

for any people, even the barbarians themselves sacrifice at its altars. So what

benefits will France gain from this beautiful colony if the government manages

it with the broad and philanthropic principles that alone can foster unity

between the conquered and the conqueror!

Ben-OmarBen-Omar, the former bey of

Titeri, remains our faithful ally, and more powerful

than armies, his conciliatory and wise words make us new allies or strengthen

the peaceful disposition of those we have acquired.

Ben-ZegriBen-Zegri, a defector from Constantine, and the

Jew Narboni, schemers who played a significant role during previous

administrations, are now entirely disgraced and have lost the positions they

managed to retain under all regimes. Upon hearing this news, the Atlas Mountains

Arabs have shown willingness to draw closer to us, which they did not do

previously.

So, France should hasten to organize this beautiful colony, and above all, not

forget this great principle: the art of governing is not the art of

oppression.

FOREIGN COLONIES.

SAINT-THOMAS.SAINT-THOMAS.

If the colonial aristocracy contented itself with persecuting the men of color

they deem dangerous, they would only partly fulfill their mission; they must

also pursue, even in foreign lands, the unfortunate individuals who have

incurred their animosity. Aristocratic hatreds are as

tenacious as those of kings, and just as NicnolasNicnolas pursues the remnants of Poland worldwide, or Charles-AlbertCharles-Albert claims his victims everywhere, colonial

aristocracy also roars with fury when an unfortunate soul condemned to the

executioner manages to escape it. Their minions track down such individuals

everywhere, and if treaties, which they can render as flexible as laws, provide

a means, extradition satisfies their thirst for mulatto blood and their

obsession with punishment.

After the events of the Grand'Anse, a man of color, Mr.

Auguste HavreMr.

Auguste Havre, took refuge on the Danish island of Saint-ThomasSaint-Thomas, espérant y trouver un asile où ses

persécuteurs ne viendraient pas le troubler. Son erreur était grande !

Mr. Morin, the son of a pharmacist from Saint-PierreSaint-Pierre, went to Saint Thomas, recognized him,

and this young colonist reported him as a supporter of the Grand'Anse revolution

to Admiral MackauAdmiral Mackau, Admiral Mackau, the

commander of the Antilles station, who happened to be in that Danish colony at

the time. This admiral who, for good reasons, shares colonial prejudices,

requested the extradition of Mr. Auguste Havre in order to hand him over to the

authorities in Martinique. He may well obtain it from the Danish government

which, despite its usual gentleness, may be influenced by the fear of

displeasing the French Ministry of the Navy.

However, one must hope that the Saint Thomas government will be dignified enough

not to sacrifice the peace and lives of the unfortunate individuals who come to

its shores to the demands of a faction. Where would we be if the sacred laws of

hospitality could be violated with impunity?

SAINT-LUCIA.SAINT-LUCIA.